The stomach, saliva, and mouth are parts two and three of my five-part series on digestion. Bruce Lee said, “Fear comes from uncertainty; we can eliminate the fear within us when we know ourselves better.” As a doctor and digestion coach of 36+ years, I will teach you to know yourself better so that fear about health and sickness is more straightforward to confront.

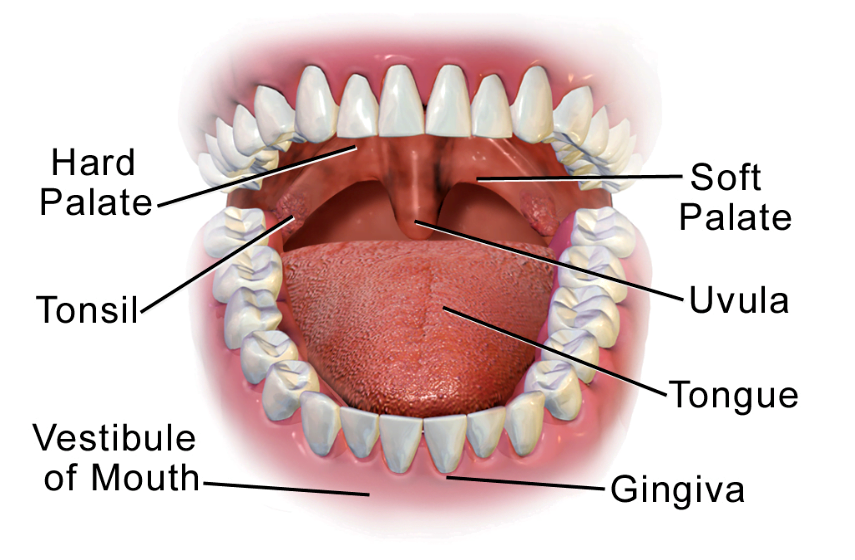

The Mouth in Digestion: Expanded Analysis

The mouth plays a pivotal role in the digestive process, representing the only phase of digestion over which we have direct, voluntary control. From the moment food enters our mouths to the point of swallowing, our actions significantly influence the efficiency of downstream digestive events. Despite this brief window of voluntary participation, our choices during this stage carry profound implications for our overall health and digestion. It is crucial to understand that digestion does not begin in the stomach but in the mouth—a fact often overlooked in health and nutrition discussions. Stress, which affects digestion by altering physiological rhythms, can negatively impact this phase by encouraging rapid eating and inadequate chewing, leaving downstream systems overwhelmed and less effective.

Importance of Proper Chewing: A Biochemical Perspective

Chewing, or mastication, serves a dual purpose: mechanically breaking down food and chemically priming it for further digestion. The physical act of chewing reduces food into smaller particles, increasing its surface area for enzyme activity and facilitating its safe passage through the esophagus. This is particularly critical for preventing conditions like esophageal reflux or choking. However, when chewing is rushed, it burdens the stomach and intestines to perform mechanical breakdown tasks that should have been completed earlier. Stress-induced eating habits often exacerbate this issue, leading to inefficient digestive outcomes.

The presence of saliva during this step cannot be overstated. Saliva is a complex and dynamic secretion containing enzymes (e.g., amylase and lipase) that initiate the digestion of starches and fats, respectively. Additionally, it includes mucins for lubrication, antimicrobial agents like lysozyme, and immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies that create a barrier against pathogens. Saliva also acts as a buffering agent, neutralizing acidic or alkaline foods before they reach the stomach. Chewing food thoroughly ensures that each morsel is adequately coated in saliva, enhancing enzymatic action and protecting the gastrointestinal lining from irritation.

Connection Between Stress and Suboptimal Chewing

Modern dietary habits, characterized by hurried meals and multitasking during eating, diminish the effectiveness of chewing. Stress amplifies this behavior, activating the body’s “fight or flight” response and diverting energy from digestion. Stress-induced hormonal changes—primarily the increase in cortisol and adrenaline—can suppress saliva production. As a result, food passes through the digestive tract inadequately prepared, increasing the risk of nutrient malabsorption, bacterial overgrowth, and gastrointestinal discomfort.

Chewing and Its Link to Broader Health Issues

Chewing also plays a critical role in mitigating systemic health problems such as obesity and diabetes. Starch-heavy diets, for example, place a heavy enzymatic demand on the digestive system. When starch digestion begins in the mouth, it reduces the workload for downstream organs and improves nutrient absorption efficiency. Additionally, saliva’s buffering capacity is essential to prevent stomach lining damage from overly acidic foods, reducing the risk of gastritis. Despite these advantages, hurried eating habits undermine these protective mechanisms, underscoring the importance of conscientious chewing as the first and most accessible intervention in improving digestion.

Observations in Modern Dietary Behavior

A casual observation of eating behaviors reveals a worrying trend—many people chew their food minimally, swallowing quickly to keep pace with busy lifestyles. This neglect contributes not only to digestive inefficiencies but also to a disconnection from the act of eating, which diminishes mindfulness and satisfaction from meals. Notably, among the myriad factors influencing poor digestive health, the one most within our control is the act of chewing, highlighting the urgency of addressing this preventable issue. A conscious effort to slow down during meals can improve digestion and overall well-being.

Digestion Coach Pro Tip: Please read – Mindful Eating: The Art of Presence While You Eat

The Stomach: Expanded Analysis

The stomach is a dynamic organ, functioning as a mechanical processor and a biochemical reactor. Its primary role is to further the digestive process by converting the food we’ve chewed into a semi-liquid substance called chyme. This transformation is achieved through robust muscular contractions known as peristalsis, combined with the action of gastric secretions such as hydrochloric acid (HCl) and enzymes, including pepsin and gastric lipase. The stomach’s acidic environment supports digestion and serves as a critical barrier to microbial invasion, ensuring that most ingested pathogens are neutralized. However, stress affects digestion significantly in this phase by altering gastric secretions, disrupting motility, and impairing the stomach’s essential functions.

Mechanical and Biochemical Breakdown

The stomach walls are composed of multiple layers of smooth muscle that allow it to churn and mix ingested food efficiently. This mechanical action pulverizes food particles, reducing them to smaller sizes that maximize their exposure to digestive enzymes and acids. Hydrochloric acid, secreted by the parietal cells lining the stomach, lowers the pH to around 1.5-3.0, an environment optimal for enzymatic activity and pathogen elimination. Pepsinogen, an inactive precursor secreted by chief cells, is activated into pepsin in the acidic medium. Pepsin cleaves proteins into smaller peptides, setting the stage for further breakdown and absorption in the small intestine. Gastric lipase, while less prominent, plays a role in the initial digestion of dietary fats, which complements the action of bile and pancreatic enzymes later in digestion.

Absorption of Vital Nutrients

Although the stomach is not the primary site for nutrient absorption, it is indispensable in preparing nutrients for absorption further along the gastrointestinal tract. For instance, the stomach facilitates the absorption of vitamin B12 by producing intrinsic factor, a glycoprotein secreted by parietal cells. Without adequate intrinsic factor, vitamin B12 cannot bind and later be absorbed in the ileum. B12 is essential for red blood cell production, neurological function, and DNA synthesis, making this process critical. Stress-induced disruptions in HCl secretion can impair intrinsic factor production, leading to vitamin B12 deficiency and conditions like pernicious anemia.

Iron absorption is also indirectly influenced by the stomach. Gastric acid helps convert dietary iron from its ferric form (Fe3+) to the ferrous form (Fe2+), which is more easily absorbed in the duodenum. Insufficient HCl, a frequent consequence of stress, undermines this conversion, increasing the risk of iron-deficiency anemia. This highlights the far-reaching impact of proper gastric function on overall nutrition.

Defense Against Pathogens

The stomach’s acidic environment is one of the body’s first lines of defense against ingested pathogens. By maintaining a low pH, the stomach can neutralize many harmful bacteria, viruses, and parasites that might otherwise enter the gastrointestinal tract. However, stress compromises this protective mechanism by reducing HCl production. This decreases the stomach’s ability to digest proteins effectively and weakens its antimicrobial capacity, leaving the individual vulnerable to infections like Helicobacter pylori or gastrointestinal viral illnesses.

Stress and Its Disruptive Impact

Stress has a profound impact on the stomach’s functionality. It inhibits gastric motility, the wave-like contractions essential for mixing and advancing chyme into the small intestine. Stress-induced motility changes can manifest as delayed gastric emptying (gastroparesis) or accelerated transit (diarrhea). Chronic stress also increases the risk of gastritis by promoting the production of stress hormones like cortisol, which can heighten the stomach’s susceptibility to damage from its own acid. Over time, this may lead to gastric ulcers and abdominal pain.

When stress impairs HCl production, undigested food particles and improperly broken down proteins may linger in the stomach or pass into the intestines. This can result in complications such as small intestine bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), malabsorption of critical nutrients, and the development of inflammatory gastrointestinal conditions. Nutrient deficiencies stemming from these disruptions, including iron and vitamin B12, are particularly concerning and can lead to systemic problems like fatigue, immune dysfunction, and cognitive decline.

Holistic Implications for Health

The intricate interplay between the stomach, saliva, chewing, and the mouth in digestion underscores their collective importance. These components work harmoniously to initiate the breakdown of food, facilitate nutrient absorption, and protect the body from disease. Proper chewing and salivary function are not merely mechanical or biochemical steps; they represent the foundation of digestive efficiency and health. Moreover, the stomach’s ability to process food effectively relies heavily on the preparation that begins in the mouth. Neglecting these early stages—through hurried eating, stress, or poor habits—can contribute to a cascade of digestive challenges and broader health issues. As a GI health coach, I recognize and respect the pivotal role these processes play. If we can make conscious choices that improve our digestion, we can fortify our well-being and resilience against disease. Take your first step toward a renewed sense of well-being. Call today to arrange a complimentary 15-minute consultation. Let’s discern whether my approach aligns with your needs. I look forward to connecting with you at 714-639-4360.

COMPLEMENTARY 15-MINUTE CALL

Stress Affects Digestion: Phases of Digestion – Part 1 of the 5

The Small Intestine and Digestion – Part 4 of 5

Large Bowel and Digestion – Part 5 of 5