Table of Contents

- Introduction to SIBO and Sugar Alcohols

- What Are Sugar Alcohols?

- The Impact of Different Sugar Alcohols on SIBO Symptoms

- The Role of Sugar Alcohols in Fermentation and Bacterial Overgrowth

- Sugar Alcohols and Osmotic Effects in the Gut

- The Cycle of Sugar Alcohol Fermentation and SIBO Symptom Exacerbation

- Why Individual Tolerance to Sugar Alcohols Varies in SIBO

- Symptoms of SIBO Linked to Sugar Alcohol Consumption

- Alternative Sweeteners for SIBO Patients

- Strategies for Managing SIBO While Reducing Sugar Alcohol Intake

- Conclusion: Balancing Sugar Alcohols and SIBO

Introduction to SIBO and Sugar Alcohols

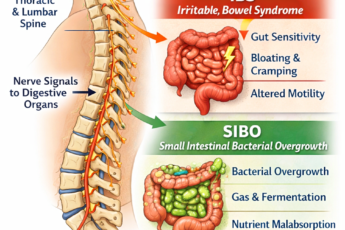

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) is a complex gastrointestinal condition characterized by excessive bacterial growth in the small intestine, a region typically designed for nutrient absorption rather than fermentation. 36+ years as a gut health expert, I have learned that a lesser-known contributor to SIBO symptoms is diet, particularly the role of sugar alcohols. These sugar substitutes, including sorbitol, xylitol, mannitol, and erythritol, are widely used in “sugar-free” products for their sweet taste and low impact on blood sugar levels. However, sugar alcohols can be highly problematic for individuals with SIBO.

Unlike traditional sugars, sugar alcohols are only partially absorbed in the small intestine. The undigested portion passes into the colon, becoming a substrate for bacterial fermentation, producing gases like hydrogen and methane. For individuals with SIBO, where bacterial overgrowth already exists in the small intestine, these sugars are an abundant fuel source for fermentation, leading to excessive gas production. This causes symptoms such as bloating and discomfort and contributes to motility disruptions, further exacerbating SIBO.

Additionally, sugar alcohols, particularly those classified as FODMAPs, such as sorbitol and mannitol, are known to trigger digestive distress in sensitive individuals. In people with SIBO, the effects are magnified as fermentation leads to gut distension and potential inflammation. This disruption can also increase gut permeability (“leaky gut”), allowing bacterial endotoxins to enter the bloodstream and aggravate systemic symptoms, further perpetuating the cycle of SIBO.

While sugar alcohols offer benefits as low-calorie sweeteners, they may worsen SIBO by fueling bacterial overgrowth and triggering gastrointestinal symptoms. For those managing SIBO, minimizing or avoiding sugar alcohols and opting for gut-friendly alternatives can be vital steps toward reducing symptom severity and restoring digestive health. Understanding the unique impact of these substances on the small intestine is crucial for effective dietary planning and SIBO management.

What Are Sugar Alcohols?

Sugar alcohols, known as polyols and the “P” in FODMAP, are a unique category of carbohydrates chemically similar to sugars and alcohols. Yet, they do not fall neatly into either category. Structurally, they contain hydroxyl (OH) groups, which are similar to those in alcohol molecules, alongside an arrangement of carbon atoms and oxygen that resembles sugars. This distinctive composition allows sugar alcohols to offer a sweet taste while containing fewer calories than regular sugar, making them popular as low-calorie sweeteners in products like sugar-free gum, candies, ice creams, and even some processed foods marketed as “sugar-free” or “low-carb.” For individuals with SIBO, however, these compounds can pose specific digestive challenges due to how they interact with the gut microbiome.

The Impact of Different Sugar Alcohols on SIBO Symptoms

Although all sugar alcohols can pose challenges for those with SIBO, each one has slightly different properties in terms of absorption and fermentation:

- Sorbitol and Mannitol are sugar alcohols notorious for causing digestive distress. Both are poorly absorbed and have a robust osmotic effect, which means they readily draw water into the intestines. Sorbitol and mannitol are also highly fermentable, making them especially problematic for SIBO sufferers.

- Xylitol: Xylitol is better absorbed than sorbitol and mannitol but is only partially absorbed in the small intestine. It can feed bacteria in the small intestine, exacerbating SIBO symptoms, although it typically has a less intense osmotic effect than some other sugar alcohols.

- Erythritol: Unlike other sugar alcohols, erythritol is primarily absorbed in the small intestine and then excreted through urine, which means it does not reach the large intestine or undergo significant fermentation. This makes erythritol a potential option for individuals with SIBO, although sensitivity can vary.

- Maltitol: Maltitol is one of the sweeter sugar alcohols, almost as sweet as regular sugar. However, it is only partially absorbed in the small intestine, which can still lead to fermentation and gas production. While its sweet taste may make it appealing, its fermentability can make it highly problematic for those with SIBO.

Although each sugar alcohol behaves slightly differently in the digestive system, they all share specific properties that make them difficult to break down and absorb, especially in individuals with SIBO.

The Role of Sugar Alcohols in Fermentation and Bacterial Overgrowth

When you consume regular sugars, such as sucrose or glucose, enzymes in the small intestine quickly break them down into simpler components, which are then absorbed into the bloodstream. Sugar alcohols, on the other hand, are only partially absorbed in the small intestine. Their complex molecular structure resists breakdown by human digestive enzymes, meaning a significant portion of these compounds remain intact as they move through the digestive tract.

One of the most problematic aspects of sugar alcohols for individuals with SIBO is that they serve as a substrate for bacterial fermentation. As they pass through the small intestine, bacteria—especially those involved in SIBO—begin to ferment them. Unlike fiber, primarily fermented in the large intestine, sugar alcohols can trigger bacterial activity much earlier in the small intestine, where the bacterial load should ideally be low.

This fermentation process produces gas as a byproduct. In SIBO, this gas may include hydrogen, methane, or even hydrogen sulfide, depending on the types of bacteria that are overgrown. Each of these gases can have different effects on the gut:

- Hydrogen: Often associated with loose stools and diarrhea, hydrogen gas can lead to cramping and an urgent need to use the restroom.

- Methane: Produced by specific types of gut archaea, methane slows intestinal motility and can potentially contribute to constipation. Methane-producing bacteria are often involved in cases of methane-dominant SIBO.

- Hydrogen Sulfide: This gas is produced by certain types of bacteria and is associated with more severe symptoms, including pain. It has a distinctive rotten-egg odor. Emerging research is exploring its specific role in SIBO symptoms.

Sugar Alcohols and Osmotic Effects in the Gut

One of the key properties of sugar alcohols is their osmotic activity. Osmosis is the movement of water across a semipermeable membrane, and due to their molecular structure, sugar alcohols tend to draw water into the intestines. When sugar alcohols reach the gut, they pull water into the intestinal lumen. This can lead to a laxative effect, resulting in loose stools or diarrhea, especially in larger quantities.

For someone with SIBO, the osmotic effect can worsen symptoms by introducing additional fluid into the small intestine, potentially increasing distension and contributing to an uncomfortable feeling of fullness or bloating. This water-drawing effect also dilutes digestive enzymes, which can further impair digestion and absorption of nutrients, exacerbating malabsorption issues that are often already present in SIBO sufferers.

The Cycle of Sugar Alcohol Fermentation and SIBO Symptom Exacerbation

Each time sugar alcohols are consumed, they reinforce a cycle of bacterial overgrowth and symptom exacerbation in SIBO sufferers. Here’s how the cycle unfolds:

- Consumption of Sugar Alcohols: The patient consumes sugar alcohols in foods such as sugar-free sweets, diet drinks, or “low-carb” snacks.

- Slow Transit and Partial Absorption: Sugar alcohols move slowly through the small intestine, and their unique structure leads to incomplete absorption.

- Bacterial Fermentation: Unabsorbed sugar alcohols become a substrate for fermentation by bacteria in the small intestine, which should ideally be a low-microbial environment.

- Gas Production and Symptoms: Fermentation generates gases that can cause bloating, abdominal pain, and, depending on the gas type, constipation or diarrhea.

- Fluid Shifts and Increased Motility Issues: Osmotic effects draw fluid into the intestine, amplifying motility issues and potentially leading to diarrhea or exacerbated bloating.

- Cycle Reinforcement: Each episode of sugar alcohol fermentation reinforces the conditions that support bacterial overgrowth, worsening SIBO.

This cycle is why many SIBO specialists recommend avoiding sugar alcohols as a dietary management strategy. Their partial absorption and fermentative properties can act as a “fuel” for the bacteria residing in the small intestine, aggravating SIBO symptoms and potentially prolonging recovery.

Why Individual Tolerance to Sugar Alcohols Varies in SIBO

Interestingly, not all sugar alcohols affect individuals with SIBO in the same way, and patient tolerance levels can vary widely. For example, erythritol tends to be better tolerated by some individuals with SIBO, as it is primarily absorbed before it reaches the small intestine, resulting in less fermentation. On the other hand, sorbitol and mannitol are often highly fermentable. Due to their strong osmotic effects and tendency to serve as prime substrates for bacterial fermentation, they can cause severe bloating and diarrhea.

In clinical practice, many healthcare providers suggest that SIBO patients avoid sugar alcohols altogether until symptoms are under control. After reaching a stable point, patients may reintroduce certain polyols in small quantities, starting with those known to have a lower fermentative potential, like erythritol, to assess tolerance. However, this approach should be individualized and carried out with careful monitoring, as the introduction of even a tiny amount of sugar alcohols can trigger symptom flare-ups in highly sensitive individuals.

Symptoms of SIBO Linked to Sugar Alcohol Consumption

When SIBO sufferers consume sugar alcohols, it can trigger a cascade of digestive disturbances, which intensify the already uncomfortable symptoms associated with SIBO. This is primarily due to the unique way sugar alcohols interact with gut bacteria and the small intestine. Let’s break down these symptoms in detail.

Excessive Gas and Bloating

One of the most common symptoms experienced by SIBO sufferers who consume sugar alcohols is excessive gas and bloating. Due to their molecular structure, sugar alcohols are poorly absorbed in the small intestine; unlike glucose, which is absorbed through the intestinal wall, sugar alcohols move through the digestive tract relatively intact. In a healthy gut, this incomplete absorption might lead to minor discomfort, but in SIBO patients, the scenario is significantly intensified.

With bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine, sugar alcohols become an easily accessible food source for the bacteria. When bacteria ferment these sugar alcohols, they produce gases—specifically hydrogen, methane, and, in some cases, hydrogen sulfide. Each of these gases contributes to bloating in different ways:

- Hydrogen: Typically produced by bacteria fermenting sugars, hydrogen gas can cause abdominal swelling and cramping.

- Methane: Certain bacteria (methanogens) convert hydrogen into methane, which slows intestinal transit, potentially leading to constipation.

- Hydrogen Sulfide: This gas, often produced in smaller amounts, can cause sharp abdominal pain and discomfort.

These gases accumulate and press against the walls of the small intestine, leading to visible bloating, abdominal distention, and the feeling of fullness. Because the small intestine is not designed to handle significant bacterial populations or fermentation, SIBO sufferers may experience intense bloating, even from small amounts of sugar alcohols.

Abdominal Pain and Cramping

Abdominal pain and cramping are frequently reported symptoms when SIBO patients consume sugar alcohols. The source of this pain is multifaceted. Firstly, the physical pressure exerted by trapped gases in the small intestine can trigger pain receptors in the gut lining, causing spasms and cramps. Additionally, sugar alcohol fermentation produces acidic byproducts that can irritate the intestinal lining, heightening discomfort.

In SIBO, the small intestine is already inflamed due to bacterial overgrowth. Fermenting sugar alcohols exacerbates this inflammation, as bacterial metabolites—including organic acids—irritate the gut mucosa, intensifying pain. For many, this pain manifests as a burning or sharp cramping sensation, which can be especially pronounced after meals.

Diarrhea or Constipation

Interestingly, sugar alcohols can cause both diarrhea and constipation, depending on how an individual’s body responds. In some cases, these symptoms may even alternate, leading to a condition known as “mixed-type” SIBO.

- Diarrhea: Sugar alcohols like sorbitol and mannitol have a laxative effect. Because they draw water into the intestine, they can soften stools and lead to diarrhea. For SIBO sufferers, this process is magnified—the influx of water and rapid fermentation speed up transit time, leading to loose, watery stools. Frequent diarrhea can further inflame the gut lining, making it more challenging for SIBO patients to absorb nutrients effectively.

- Constipation: Conversely, methane-producing bacteria can lead to constipation, especially when fermenting certain sugar alcohols. Methane gas tends to slow gut motility, causing stool to move sluggishly through the digestive tract. Sugar alcohols like xylitol can contribute to gas production, exacerbating methane-dominant SIBO constipation.

Nausea and Burping

Some SIBO patients report nausea and frequent burping after consuming sugar alcohols. This symptom may be caused by gas buildup and subsequent pressure within the small intestine. When gas accumulates, it often travels upwards through the digestive tract, leading to burping to release pressure. In cases where gas cannot escape efficiently, it creates a sensation of fullness or nausea.

Furthermore, the small intestine’s slow motility, worsened by methane gas in certain SIBO patients, can result in partial food regurgitation or acid reflux, contributing to nausea. The delayed gastric emptying associated with this process creates a feeling of food “sitting” in the stomach, leading to discomfort and even vomiting in severe cases.

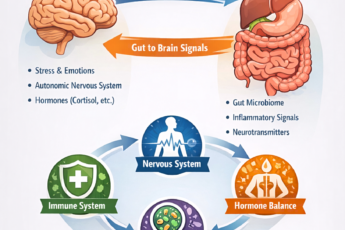

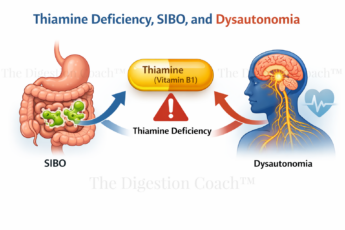

Fatigue and Brain Fog

The connection between sugar alcohols, SIBO, and cognitive symptoms may be less obvious, yet it is highly relevant. When bacteria ferment sugar alcohols in the small intestine, they produce a range of metabolites, including endotoxins. These endotoxins can cross into the bloodstream through a compromised gut lining called “leaky gut.” Once in the bloodstream, these toxic byproducts can trigger a systemic immune response, which often manifests as fatigue and cognitive dysfunction, or “brain fog.”

For SIBO sufferers, even small amounts of sugar alcohols can provoke this inflammatory response, leading to feelings of mental cloudiness, low energy, and difficulty concentrating. Chronic exposure to endotoxins can strain the body’s detoxification systems, particularly the liver, further contributing to fatigue.

Heartburn and Acid Reflux

Heartburn and acid reflux are also common symptoms in SIBO sufferers who consume sugar alcohols. The process is linked to the gas buildup that results from bacterial fermentation. Excessive gas places pressure on the stomach and lower esophageal sphincter (LES), the muscle that prevents stomach acid from entering the esophagus. When the LES is weakened or overwhelmed by this pressure, acid can flow back into the esophagus, causing a burning sensation or heartburn.

In cases of SIBO, the additional fermentation activity induced by sugar alcohols exacerbates this pressure, making acid reflux more likely. This leads to discomfort and may increase the risk of esophageal irritation and damage over time.

Disruption of Gut Motility

Sugar alcohols are also known to affect the gut’s natural motility patterns, specifically the Migrating Motor Complex (MMC). The MMC is a series of wave-like muscle contractions that move through the digestive tract in a fasting state, “sweeping” out bacteria and undigested food particles from the small intestine. In SIBO, the MMC is often impaired, allowing bacteria to remain in the small intestine, where they can cause fermentation and gas production.

- Stimulant for Abnormal Motility: Sugar alcohols, particularly sorbitol, and mannitol, can overstimulate the small intestine’s contractions. However, instead of aiding in clearing bacteria, these contractions may become disordered, leading to inconsistent motility. This erratic motility prevents the MMC from functioning effectively, allowing bacterial populations to persist and grow within the small intestine.

- Contribution to Bacterial Overgrowth: When motility is slowed or disorganized, bacteria can remain in the small intestine for extended periods. This allows for prolonged fermentation and more significant overgrowth, worsening the cycle of SIBO symptoms. The presence of sugar alcohols can thus impair motility in a way that supports bacterial overgrowth, perpetuating the problem.

Sugar alcohol intake can influence the MMC and gut motility, making it more challenging for the body to manage and reduce bacterial levels in the small intestine. This can deepen the chronic nature of SIBO.

Alteration of Gut Microbiota Composition

The selective fermentation of sugar alcohols can also alter the composition of the gut microbiota, promoting the growth of certain bacterial species that thrive on these compounds. In the context of SIBO, where the small intestine already harbors an excess of bacteria, this selective feeding can encourage bacterial strains that produce more gas or harmful metabolites, further worsening symptoms.

- Promotion of Gas-Producing Bacteria: Bacteria that thrive on sugar alcohols often produce hydrogen or methane gas. When these bacteria receive an influx of sugar alcohols, they proliferate more rapidly, increasing the overall gas production. For SIBO sufferers, this growth of gas-producing bacteria leads to more bloating, discomfort, and alterations in bowel habits.

- Impact on Gut pH and Inflammation: The fermentation process of sugar alcohols produces acids that lower the pH in the gut. A more acidic environment can support the growth of bacteria that further disrupt the gut lining, leading to inflammation. This low-grade inflammation may contribute to symptoms like cramping and gut pain and can damage the integrity of the gut barrier, creating a situation known as “leaky gut.” Leaky gut, in turn, can allow bacterial endotoxins to enter the bloodstream, leading to systemic inflammation and symptoms like fatigue and brain fog.

Thus, sugar alcohol consumption can directly influence the bacterial profile in the small intestine, encouraging the proliferation of bacteria that exacerbate SIBO symptoms and contribute to inflammation.

Increased Risk of Small Intestinal Inflammation and Mucosal Damage

Finally, repeated exposure to sugar alcohols may increase the risk of inflammation and mucosal damage in the small intestine. The acidic byproducts of bacterial fermentation, coupled with the osmotic effects of sugar alcohols, can damage the mucosal lining over time, leading to inflammation and increased intestinal barrier permeability.

- Erosion of the Mucosal Barrier: Sugar alcohol fermentation produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and other organic acids that can erode the mucosal lining. For SIBO patients, whose mucosal lining may already be compromised, this erosion can make the gut wall more susceptible to irritation and inflammation.

- Permeability, Inflammation, and Immune Activation: A compromised gut barrier, “Leaky Gut,” does not only cause local inflammation and can trigger immune responses throughout the body. This systemic inflammation can exacerbate symptoms beyond the digestive system, including fatigue, skin issues, and even cognitive symptoms like brain fog, which many SIBO sufferers experience.

Enhanced Production of Harmful Byproducts

As bacteria metabolize sugar alcohols, they produce gas and other byproducts that can negatively impact gut health and exacerbate SIBO symptoms.

- Acidic Byproducts: The fermentation of sugar alcohols produces SCFAs, such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate. While these SCFAs can be beneficial in the large intestine, in the small intestine, they can lower the pH and create an environment that irritates the gut lining. This acidic environment is particularly problematic in SIBO, as it can trigger inflammation and damage the mucosal barrier, worsening symptoms such as pain, bloating, and food sensitivities.

- Endotoxin Production: Some bacteria, particularly certain Gram-negative species, release endotoxins as they grow and divide. When sugar alcohols feed these bacteria, the increased population can lead to more endotoxin release. If the intestinal barrier is compromised (a condition often called “leaky gut”), endotoxins can penetrate the bloodstream and trigger a systemic inflammatory response. For SIBO sufferers, this means that sugar alcohols not only worsen gut symptoms but may also contribute to symptoms such as fatigue, brain fog, and joint pain.

- Hydrogen Sulfide Production: In specific individuals, sugar alcohols can feed bacteria that produce hydrogen sulfide, a gas known for its pungent “rotten egg” smell. In SIBO patients, high levels of hydrogen sulfide can contribute to particularly unpleasant and often sulfur-smelling gas, along with increased abdominal pain and gut irritation. Hydrogen sulfide can also be toxic in high concentrations, damaging the gut lining and contributing to mucosal inflammation.

By promoting the production of these harmful byproducts, sugar alcohols can significantly worsen SIBO symptoms and contribute to a more inflammatory gut environment.

Disruption of the Migrating Motor Complex (MMC)

The Migrating Motor Complex (MMC) is vital in preventing bacterial overgrowth by “sweeping” undigested food and bacteria out of the small intestine during fasting periods. Disruption of this system is already an issue in SIBO, and sugar alcohols can further complicate MMC function.

- Stimulant Effect on Gut Contractions: Sugar alcohols, due to their osmotic properties, can stimulate gut contractions. However, this stimulation does not necessarily promote effective motility; it often leads to erratic or disordered contractions that do not effectively clear the small intestine. This can allow bacteria to linger and further proliferate.

- Interference with MMC Activation: Prolonging the time food and sugar alcohols remain in the small intestine exacerbates bacterial overgrowth. If the MMC fails to clear out bacteria effectively, the small intestine remains populated with fermentative bacteria that thrive on sugar alcohols, perpetuating the cycle of SIBO symptoms.

This effect on motility, combined with the selective feeding of certain bacteria, can create a feedback loop that worsens bacterial overgrowth and intensifies symptoms in SIBO patients.

Alternative Sweeteners for SIBO Patients

Effectively managing SIBO often involves rethinking dietary choices, especially those related to carbohydrates and sweeteners that fuel bacterial fermentation. Standard sugars and many sugar alcohols tend to exacerbate SIBO symptoms by lingering in the small intestine, providing bacteria with fermentable material. However, several alternative sweeteners can satisfy a sweet craving while minimizing the risk of feeding unwanted bacteria in the small intestine. Let’s take a closer look at some of the most suitable options.

Stevia

Stevia is a popular plant-based sweetener extracted from the leaves of Stevia rebaudiana. Its non-carbohydrate and non-fermentable chemical structure makes it uniquely suitable for SIBO patients.

- Non-Carbohydrate Structure: Unlike sugar or sugar alcohols, stevia doesn’t contain fermentable carbohydrates. Its active compounds, steviosides and rebaudiosides, are glycosides that pass through the digestive system primarily unaltered. This means bacteria in the small intestine don’t have the opportunity to break down and ferment it into gases or other byproducts that could worsen SIBO symptoms.

- Metabolism and Absorption: Most stevia is absorbed in the upper part of the digestive tract, bypassing the small intestine where SIBO bacteria reside. After absorption, steviosides are broken down into steviol and excreted through urine without undergoing significant fermentation in the gut. This mechanism reduces the risk of any residual sweetener-feeding bacterial overgrowth.

- Impact on Insulin and Blood Sugar: Stevia also has minimal to no effect on blood sugar levels, which benefits those managing both SIBO and blood sugar dysregulation. The stability in blood sugar also means it doesn’t drive cravings, making it easier for individuals to control their carbohydrate intake, a key aspect of SIBO management.

Monk Fruit (Luo Han Guo)

Monk fruit, derived from the Siraitia grosvenorii plant, is another natural sweetener generally safe for SIBO patients due to its low fermentation potential and lack of impact on gut bacteria.

- Non-Fermentable Mogrosides: The sweetness in monk fruit comes from mogrosides, compounds that are glycosides similar to those in stevia. These mogrosides are metabolized differently than typical sugars, meaning they don’t act as a substrate for bacterial fermentation. As a result, monk fruit doesn’t contribute to gas production or bloating, making it a well-tolerated choice for SIBO sufferers.

- Highly Concentrated Sweetness: Monk fruit is extremely sweet in its natural form, often hundreds of times sweeter than table sugar. Small quantities can be used, further reducing the amount of potential residual compounds entering the gut and interacting with the microbiome.

- Antioxidant Properties: Research has shown that mogrosides may also have antioxidant properties, which can reduce inflammation in the digestive tract. Although this doesn’t directly affect SIBO, minimizing inflammation can support overall gut health and resilience, especially if the gut lining is compromised by bacterial overgrowth.

Erythritol (with Caution)

Due to its unique absorption profile, erythritol is one of the few sugar alcohols that SIBO patients may tolerate well in small amounts. Unlike other sugar alcohols, erythritol is absorbed almost entirely in the upper digestive tract, leaving very little in the small intestine to interact with bacteria.

- Non-Fermentable and High Absorption Rate: Erythritol is approximately 90% absorbed in the small intestine, meaning it rarely reaches the colon or interacts with bacteria that could ferment it. As a result, it produces little to no gas. This sets erythritol apart from other sugar alcohols like sorbitol or maltitol, which are only partially absorbed and can significantly exacerbate SIBO symptoms.

- Osmotic Effect Caution: While erythritol generally doesn’t feed bacteria, it can have a mild osmotic effect, meaning it draws water into the digestive tract. This can occasionally cause bloating or loose stools in sensitive individuals, so using erythritol in moderate quantities and observing any personal tolerance level is advisable.

- Taste and Compatibility: Erythritol has a similar taste profile to sugar and blends well with other low-fermentable sweeteners, such as stevia. This compatibility allows SIBO sufferers to create a sugar-like taste without the digestive drawbacks associated with standard sugars or other sugar alcohols.

Allulose

Allulose is a “rare sugar” found in small amounts in foods like figs and raisins. Structurally, it resembles fructose but behaves differently in the body. It is mainly excreted without metabolizing or absorbed by small intestine bacteria.

- Low-Calorie and Non-Fermentable: Due to its unique structure, gut bacteria do not utilize allulose as an energy source. This minimizes the risk of bacterial fermentation and gas production, making it particularly compatible with those with SIBO.

- Minimal Blood Sugar Impact: Like stevia and monk fruit, allulose has little impact on blood sugar levels. This helps avoid spikes in blood sugar that can lead to cravings or indirectly disrupt the gut’s microbial balance.

- Thermal Stability: Allulose can be used in cooking and baking, making it a versatile option for SIBO patients looking to avoid sugar without compromising on taste or recipe quality. Since it doesn’t undergo fermentation, it remains safe for SIBO sufferers even when used in prepared foods.

Aspartame (with Consideration)

Though often viewed with caution, aspartame, an artificial sweetener, may be a viable option for SIBO sufferers in limited amounts. It is fully absorbed in the upper digestive tract, meaning it doesn’t interact with bacteria in the small intestine.

- Complete Absorption: Aspartame is digested into its component amino acids—phenylalanine, aspartic acid, and methanol—before reaching the gut bacteria. This complete absorption prevents fermentation, making it a non-contributing factor to gas or bloating in SIBO.

- Caloric and Carbohydrate-Free: Aspartame doesn’t contain carbohydrates, which can benefit those aiming to control their intake of fermentable substrates. Additionally, it doesn’t contribute to blood sugar spikes or cravings, making adhering to a SIBO-friendly diet easier.

- Limitations and Cautions: While aspartame is non-fermentable, it’s not without potential side effects, especially for individuals sensitive to phenylalanine. Those with phenylketonuria (PKU) or specific metabolic sensitivities should avoid aspartame. Furthermore, excessive consumption may still affect gut health indirectly, so it’s best used sparingly.

Saccharin

Saccharin, another artificial sweetener, has a long history of use and is generally non-fermentable in the gut, making it an option worth considering for SIBO patients.

- Chemical Stability and Non-Fermentable: Saccharin is highly stable and not broken down by gut bacteria. Thus, it doesn’t contribute to fermentation or gas production in the small intestine, making it less likely to aggravate SIBO symptoms.

- Blending with Other Sweeteners: Saccharin can have a slightly bitter aftertaste when used alone, but it blends well with other non-fermentable sweeteners like stevia or erythritol. This allows SIBO patients to customize their sweetener choices while avoiding common triggers.

- Moderation is Key: Although saccharin doesn’t directly contribute to SIBO, excessive use can still influence gut motility and taste receptors. Therefore, it’s best to use it in moderation to avoid any unintended effects on digestion.

Alternative Sweeteners for SIBO Patients

For those managing SIBO, the choice of sweetener can make a significant difference in symptoms and overall gut health. Here are a few practical tips for incorporating these alternatives:

- Test Individual Tolerance: Everyone’s gut microbiome is different, and even non-fermentable sweeteners can sometimes lead to discomfort. Try small amounts of a new sweetener and monitor for any symptoms.

- Combine Sweeteners for Balanced Flavor: Blending stevia, monk fruit, or erythritol in small amounts can create a balanced sweetness with fewer side effects, reducing the need for any single sweetener in high quantities.

- Avoid Overconsumption: Even SIBO-friendly sweeteners can impact gut health if consumed excessively. Moderation helps maintain balance and minimizes unintended impacts on motility or microbiome composition.

- Pay Attention to Ingredients: Some commercial sweeteners are mixed with fillers or sugar alcohols that can exacerbate SIBO. Always read labels and opt for pure forms of these sweeteners.

Strategies for Managing SIBO While Reducing Sugar Alcohol Intake

Managing Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO) is challenging due to the small intestine’s sensitivity to fermentable substances that can fuel bacterial proliferation. Sugar alcohols are highly fermentable for certain gut bacteria, so they can significantly aggravate symptoms in those with SIBO, including bloating, abdominal pain, and irregular bowel movements. Thus, an essential strategy in controlling SIBO involves either minimizing or completely avoiding sugar alcohols while implementing other dietary and lifestyle adjustments to stabilize and support gut health. Working with a SIBO Specialist can take a lot of stress out of this journey and save time and money.

1. Identify Common Sugar Alcohols in Your Diet

The first step in reducing sugar alcohol intake is to become aware of the various sugar alcohols in processed foods, sweeteners, and even some dietary supplements. Sugar alcohols such as sorbitol, xylitol, maltitol, mannitol, and erythritol are common additives that replace sugar in “low-calorie” or “sugar-free” products. Each has varying impacts on the gut, but most sugar alcohols are only partially absorbed in the small intestine, where they can fuel unwanted bacterial growth.

- Label Reading: Familiarize yourself with ingredient lists, looking specifically for sugar alcohols. Many products labeled “sugar-free” or “low-calorie” rely on these compounds as primary sweeteners. Sugar alcohols can also be found in unexpected places, such as medications, chewing gum, protein bars, and even some supplements.

- Check for Common Additives: It’s also helpful to note that sugar alcohols may be accompanied by other additives or fibers that could similarly impact the gut, such as inulin or FOS (fructooligosaccharides), which are also highly fermentable.

2. Implement a Low-FODMAP Diet

A low-FODMAP diet has been one of the most effective dietary strategies for managing SIBO symptoms. FODMAPs (Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols) are a group of carbohydrates, including sugar alcohols (polyols), that are poorly absorbed in the small intestine and highly fermentable by gut bacteria.

- Focus on Low-FODMAP Foods: In a low-FODMAP approach, foods high in fermentable compounds are either limited or avoided to reduce bacterial activity and fermentation. Sugar alcohols fall within the polyol category, so minimizing or eliminating them can be an essential aspect of managing SIBO.

- Dietary Reintroduction Process: A structured reintroduction phase can also help you identify specific trigger foods or compounds, like particular sugar alcohols, that may exacerbate symptoms. After a period of low-FODMAP eating, foods are reintroduced one by one to gauge tolerance levels. This process allows a more personalized understanding of your unique gut sensitivity profile.

3. Focus on Easily Digestible Carbohydrates

For SIBO patients, choosing carbohydrates quickly and easily absorbed in the small intestine can limit the fermentable material available to bacteria. Unlike sugar alcohols, which linger in the small intestine, certain carbohydrates are absorbed more efficiently, thus bypassing the conditions that fuel SIBO.

- Simple, Non-Fermentable Carbohydrates: Foods like white rice, potatoes, and certain fruits (like bananas and berries) contain simple carbohydrates absorbed earlier in the digestive tract, reducing the risk of feeding bacteria in the small intestine.

- Avoid Complex Fibers and Resistant Starches: Foods rich in complex fibers or resistant starches tend to escape early digestion and may become fuel sources for bacteria later in the gut. Limiting these can help stabilize the gut environment and reduce fermentation risks.

4. Integrate Alternative Sweeteners Wisely

Replacing sugar alcohols with non-fermentable sweeteners like stevia, monk fruit, or allulose can offer a safer option for those managing SIBO. These sweeteners are either minimally fermentable or entirely non-fermentable, reducing the likelihood of bacterial feeding in the small intestine.

- Monitor Tolerance: Some SIBO sufferers may tolerate small amounts of erythritol, though this should be tested individually due to its partial absorption rate. Erythritol is one of the few sugar alcohols primarily absorbed in the upper digestive tract, reducing its fermentability, but it still poses a risk in high quantities.

- Avoiding Artificial Sweeteners in High Quantities: Some artificial sweeteners (e.g., aspartame and saccharin) may disrupt gut motility and microbiome balance, so it’s best to use natural non-fermentable sweeteners in moderation.

5. Implement Meal Timing and Spacing

Allowing ample time between meals is another effective way to reduce fermentation and bacterial overgrowth. Known as the Migrating Motor Complex (MMC), a natural “cleaning wave” occurs in the small intestine approximately 90 minutes after eating, sweeping residual food and bacteria toward the colon. Frequent snacking or grazing can disrupt this process, accumulating food in the small intestine, which feeds bacterial growth.

- Try Intermittent fasting or time-restricted eating. This approach can enhance the efficiency of the MMC by limiting meals to specific time windows. It allows the MMC more time to function between meals, thus reducing the material available for fermentation.

- Extend Meal Spacing: Aim for at least 4-5 hours between meals. This window provides ample time for the MMC to work, reducing the likelihood that any undigested material in the small intestine becomes fuel for bacteria.

6. Support Digestion with Digestive Enzymes

Digestive enzymes can help ensure that food is broken down efficiently in the upper digestive tract, reducing the residue that reaches the small intestine and minimizing fermentation risk.

- Protease, Amylase, and Lipase Enzymes: These enzymes break down proteins, carbohydrates, and fats, respectively. By improving breakdown efficiency, you can reduce the amount of undigested food that reaches the small intestine and fuels SIBO-related bacterial overgrowth.

- Betaine HCl for Stomach Acidity: For those with low stomach acid, Betaine HCl can support proper protein digestion, preventing the escape of undigested protein fragments to the small intestine. Proper stomach acidity also acts as a barrier, reducing bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine.

7. Increase Dietary Diversity and Prebiotic Caution

While fiber and prebiotics are generally considered beneficial for gut health, their fermentable nature can often exacerbate symptoms in SIBO sufferers. However, certain low-fermentable fibers may be tolerated in small amounts and help diversify the gut microbiome, supporting resilience.

- Select Low-Fermentable Fibers: Foods like chia seeds, flaxseeds, and small quantities of soluble fibers can provide gentle support for the gut without overly feeding bacteria. You may need to test tolerance gradually and carefully.

- Avoid High-FODMAP Prebiotics: inulin, fructooligosaccharides (FOS), and galactooligosaccharides (GOS) are high-FODMAP fibers that can promote bacterial growth in the small intestine. Opting for lower-FODMAP prebiotics or avoiding prebiotics altogether may reduce symptom aggravation.

8. Explore Probiotic Therapy Carefully

Probiotics are a valuable tool for gut health, but in SIBO, they need to be used cautiously as some can worsen bacterial imbalance in the small intestine. Certain strains are more suitable for SIBO management and can help rebalance gut flora without promoting excessive bacterial overgrowth.

- Consider Soil-Based Probiotics: Soil-based probiotics contain spore-forming bacteria like Bacillus species, which benefit some SIBO sufferers without overpopulating the small intestine. These strains pass through the digestive tract without lingering, reducing the risk of promoting bacterial overgrowth.

- Single-Strain vs. Multi-Strain Options: In SIBO, single-strain probiotics may be preferable to multi-strain options, as multi-strain formulas can introduce various bacteria that might exacerbate symptoms. Lactobacillus reuteri and Bacillus coagulans have shown promise for certain SIBO cases.

9. Regular Gut Health Monitoring

Managing SIBO is often a long-term commitment, so regular monitoring with a healthcare provider can help track progress and adapt strategies as needed.

- Breath Testing: Regular hydrogen or methane breath testing can help gauge the levels of bacterial overgrowth and determine how effectively SIBO is being managed. Testing every few months can provide valuable insights into symptom patterns and guide dietary adjustments.

- Symptom Journaling: Documenting daily symptoms, dietary choices, and sweetener intake can help you identify trends and potential triggers. Over time, you’ll better understand your tolerance to sugar alcohols and other fermentable compounds.

Conclusion: Balancing Sugar Alcohols and SIBO

As a doctor specializing in digestive issues, especially SIBO, one of my goals in managing Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO), is achieving balance—particularly regarding dietary triggers like sugar alcohols. It’s essential for both symptom control and long-term gut health. Though often marketed as a healthier, lower-calorie alternative to traditional sugars, sugar alcohols can have significant repercussions for individuals with SIBO due to their fermentative potential in the gut. As a result, these sweeteners require a cautious, individualized approach.

For SIBO sufferers, the goal should not be to adopt an overly restrictive diet indefinitely. Instead, understanding and recognizing the specific triggers that exacerbate SIBO symptoms allows for a more sustainable and personalized plan. While some people with SIBO may find that they need to avoid sugar alcohols altogether, others might tolerate them in limited quantities. The key is awareness and adaptability: recognizing which sugar alcohols are more fermentable, experimenting cautiously with portion sizes, and observing personal tolerance can allow for more dietary flexibility without compromising gut health.

The Importance of a Targeted Approach

Being a digestion coach, I know every individual’s digestive system is unique, and a one-size-fits-all approach is rarely effective for SIBO management. Sugar alcohols like sorbitol, mannitol, xylitol, and erythritol each have distinct pathways of fermentation and absorption in the gut, and understanding these mechanisms provides a foundation for making informed dietary choices. For instance, sorbitol and mannitol are highly fermentable and can exacerbate gas, bloating, and discomfort. While less fermentable than others, Xylitol can still disrupt gut bacteria when consumed in excess. On the other hand, Erythritol has a unique metabolic profile. It is mainly absorbed in the small intestine and excreted unchanged, making it less likely to cause immediate SIBO symptoms, although individual responses still vary.

Incorporating these insights allows for a targeted approach that considers the potential for fermentation, each individual’s tolerance levels, and digestive health status. It’s often helpful to experiment with various sugar alcohols under the guidance of a healthcare provider, noting any symptoms and adjusting intake accordingly. This careful process of trial and observation supports a balanced approach to sugar alternatives without the need for overly restrictive measures.

Balancing the Gut Microbiome

A balanced microbiome is essential for managing SIBO and minimizing the risk of relapse. When sugar alcohols disrupt this balance through rapid fermentation or altered bacterial interactions, the resulting environment can promote bacterial overgrowth. Dietary adjustments that support beneficial bacterial populations—rather than triggering excessive fermentation—are invaluable for long-term management.

Supporting microbial diversity may involve incorporating low-FODMAP prebiotics, well-tolerated fibers, and even selected probiotics into a broader gut health regimen. Limiting sugar alcohols is only one part of the equation; nurturing the microbiome with foods and supplements that encourage the growth of healthy bacteria also plays a critical role. By focusing on bacterial balance and diversity, it’s possible to create an intestinal environment that is less hospitable to SIBO, ultimately reducing symptom recurrence.

A Holistic View of SIBO Management

Successful long-term SIBO management requires a holistic approach that incorporates diet, lifestyle, and targeted therapies. Beyond food choices, factors like gut motility, stress management, immune support, and gut barrier function influence SIBO’s trajectory. Managing sugar alcohols is a powerful tool in this multifaceted approach, but it should be used alongside other strategies that support digestion and minimize bacterial overgrowth.

For many, this approach means prioritizing a diet rich in whole, unprocessed foods that limit fermentable sugars and fibers without depriving the body of essential nutrients. This balance, in conjunction with stress management, regular motility support, and specific supplements as needed, creates a foundation for digestive health and symptom control.

Moving Forward with Confidence

I treated my first SIBO patient in the mid-90s before the term SIBO was coined. This version of IBS has changed over the years, becoming more common and more complex to treat. Managing SIBO and its sufferers now demands continuous learning and adaptation. By gaining a deeper understanding of the interactions between sugar alcohols and the gut, SIBO sufferers can feel confident that there are doctors who understand the many facets of SIBO and SIBO management. With guidance, SIBO patients can make informed choices that empower them to manage symptoms while enjoying a varied diet. This empowerment comes not from strict avoidance but from knowledge: knowing how various compounds impact gut bacteria, which foods to limit or enjoy in moderation, and how to adjust habits in response to symptoms.

Ultimately, the balance lies in being proactive without being overly restrictive. By focusing on gut health holistically and mindfully incorporating—or avoiding—sugar alcohols, it’s possible to maintain a sustainable dietary approach that minimizes SIBO symptoms and promotes a healthy digestive system.

With patience, self-awareness, and informed choices, managing SIBO can shift from an overwhelming struggle to a balanced, manageable routine.

COMPLEMENTARY 15-MINUTE CALL

Take your first step toward a renewed sense of well-being. Call today to arrange a complimentary 15-minute consultation.

Let’s discern whether my approach aligns with your needs.

I look forward to connecting with you at 714-639-4360.