Table of Contents

- Understanding Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)

- Causes of SIBO

- The Consequences to the Gut Lining

- SIBO’s Effect on Systemic Health

- The Role of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in SIBO Treatment

- The SIBO Cycle: Why Is Hard to Treat

Understanding Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO)

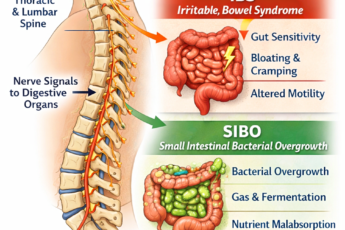

Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth, or SIBO, is a complex condition where the small intestine becomes excessively populated by bacteria, often species more typical of the large intestine. To understand why this overgrowth is so problematic, let’s first take a closer look at the unique structure and function of the small intestine.

The small intestine is a highly specialized organ designed primarily for nutrient absorption. It has a unique environment with a low bacterial load compared to the large intestine. Its long, narrow structure, combined with regular contractions (known as peristalsis), typically moves food swiftly from the stomach to the colon. These contractions also help to limit bacterial colonization by pushing microbes downstream. The small intestine is not built for fermentation — a function reserved primarily for the large intestine, where large colonies of bacteria work to break down fiber and other residual nutrients.

In SIBO, this balance is disrupted. Excessive or inappropriate bacteria populate the small intestine, leading to fermentation processes in an unequipped area to handle them. The presence of these bacteria in high numbers can cause a range of symptoms, including bloating, gas, abdominal pain, and malabsorption of nutrients. Over time, these effects can lead to significant health issues, as the small intestine’s absorptive functions are impaired, and local inflammation can damage the gut lining.

Causes of SIBO

SIBO often results from acute and chronic factors impairing the small intestine’s natural clearing mechanisms. Here is a list of primary and secondary causes:

Impaired Motility

The small intestine relies on the migrating motor complex (MMC) to sweep food particles, bacteria, and waste products out of the gut during fasting periods. Impaired motility disrupts this cleaning mechanism, allowing bacteria to accumulate. Conditions like diabetes, hypothyroidism, and scleroderma can hinder gut motility. Certain medications, such as opioids, may also slow this process, exacerbating bacterial overgrowth by providing a stagnant environment conducive to microbial proliferation.

Structural Abnormalities

Structural abnormalities in the gastrointestinal tract can trap food or alter the normal flow, leading to bacterial overgrowth. Examples include small intestinal strictures caused by Crohn’s disease, adhesions from previous surgeries, or diverticula (outpouchings of the intestinal wall). These abnormalities create pockets or blockages, restricting the natural movement of food and fostering the environment for SIBO.

Low Stomach Acid (HCl)

Hydrochloric acid in the stomach is critical in sterilizing ingested food and preventing harmful bacterial colonization in the small intestine. When acid levels are low, a condition known as hypochlorhydria, bacteria that typically die in the stomach may thrive and move into the small intestine. Causes of low stomach acid include prolonged proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use, aging, H. pylori infection, or autoimmune conditions like pernicious anemia.

Immune System Imbalance

A compromised immune system can reduce the capacity to regulate gut bacterial populations. Immune suppression from conditions like HIV, chronic stress, or immune-modulating medications (e.g., corticosteroids) can reduce the ability to clear bacteria efficiently from the gut. Additionally, autoimmune diseases may interfere with intestinal immune function, disrupting the balance between beneficial and pathogenic bacteria.

Chronic Use of Sugar Alcohols (Polyols)

Sugar alcohols, commonly found in low-calorie foods and artificial sweeteners, can ferment in the gut, feeding bacteria and encouraging bacterial overgrowth. In individuals predisposed to poor absorption of polyols (e.g., sorbitol, mannitol), these compounds can accumulate in the small intestine, worsening symptoms like bloating, diarrhea, and gas associated with SIBO.

Acute Food Poisoning

Studies indicate that food poisoning, traveler’s diarrhea, or acute bacterial gastroenteritis can lead to post-infectious IBS (Irritable Bowel Syndrome) in approximately 10% of cases. Many instances of post-infectious IBS are actually forms of SIBO (Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth). During these infections, the immune system may create antibodies against toxins produced by the bacteria responsible for the acute symptoms, such as diarrhea or vomiting. While the original pathogens—such as Campylobacter, abnormal strains of E. coli, or Salmonella—are usually eliminated, these antibodies can persist for years, impairing gut motility and contributing to chronic SIBO.

Antibiotic Use

While antibiotics can eliminate harmful pathogens, they also disrupt the balance of the gut microbiome by killing beneficial bacteria. This microbial imbalance can create an opportunity for harmful bacterial overgrowth. Additionally, overuse or improper use of antibiotics may contribute to antibiotic-resistant strains that exacerbate the problem.

Dysfunctional Ileocecal Valve

The ileocecal valve, which separates the small intestine from the colon, is vital in preventing bacteria from the large intestine from migrating into the small intestine. If this valve is dysfunctional or damaged—due to chronic inflammation, surgical procedures, or congenital abnormalities—colon bacteria can backflow into the small intestine, leading to SIBO.

Chronic Stress

Chronic stress significantly affects gut function by altering the gut-brain axis, a bidirectional communication system between the brain and the gastrointestinal tract. Stress-induced changes in hormone levels, such as elevated cortisol, can disrupt gut motility, suppress immune responses, and impair the intestinal barrier, leading to “leaky gut.” These factors create an environment conducive to bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine. Additionally, stress often alters eating habits and the diversity of gut microbes, compounding the risk of developing SIBO.

Dietary Habits

Dietary patterns can play a pivotal role in the development of SIBO. Frequent snacking or a high carbohydrate diet limits the fasting periods needed to activate the migrating motor complex (MMC), the gut’s natural cleaning mechanism. Food remnants and bacteria remain in the small intestine without adequate MMC activation, encouraging bacterial growth. Additionally, diets rich in fermentable carbohydrates may further fuel these bacteria, worsening symptoms like bloating and gas.

Connective Tissue Disorders

Connective tissue disorders, such as scleroderma and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome (EDS), can compromise the structural integrity of the gastrointestinal tract. Weak or hypermobile connective tissues in the intestinal walls can lead to abnormal gut motility and the formation of pockets or areas prone to stasis, where bacteria can proliferate. Individuals with such disorders may also have impaired function of the ileocecal valve and the autonomic nervous system, further predisposing them to SIBO.

Radiation Therapy or Chemotherapy

Cancer treatments such as radiation therapy and chemotherapy can damage the intestinal lining, slow gut motility, and disrupt the microbiome. These therapies weaken the immune system, reduce the diversity of beneficial gut bacteria, and may result in chronic inflammation, creating fertile ground for bacterial overgrowth. Long-term changes to the intestinal environment due to treatment side effects make managing and recovering from SIBO more challenging.

Endometriosis or Abdominal Adhesions

Endometriosis and abdominal adhesions, which can result from surgeries or inflammation, often distort the normal structure and function of the gastrointestinal tract. Adhesions or endometrial growths on the intestines can physically impair gut motility, create areas of obstruction or stasis, and alter the distribution of gut bacteria. This altered anatomy traps bacteria and food particles, fostering an environment that promotes bacterial overgrowth, making these conditions a significant risk factor for SIBO.

The Consequences to the Gut Lining

Over time, SIBO can compromise the integrity of the gut lining, leading to a condition known as increased intestinal permeability or “leaky gut.” The small intestine has a selectively permeable lining that allows specific molecules (like digested nutrients) through while blocking larger, potentially harmful substances. However, as the bacteria in SIBO overpopulate and ferment food particles, they release endotoxins, such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS), which can irritate and inflame the gut lining.

Chronic exposure to these endotoxins, combined with the inflammation from bacterial overgrowth, can weaken the tight junctions between the cells lining the small intestine. This weakening allows larger particles, including partially digested food, bacteria, and toxins, to “leak” into the bloodstream, triggering immune responses and systemic inflammation. Due to the gut-brain connection, this phenomenon can contribute to symptoms beyond the digestive system, such as fatigue, joint pain, and cognitive symptoms.

SIBO’s Effect on Systemic Health

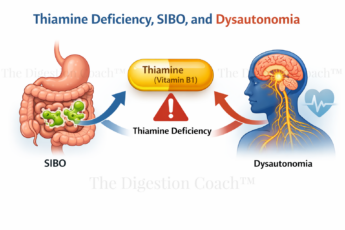

As the gut lining is compromised, SIBO can have far-reaching effects on systemic health. The immune system may start reacting to food particles that “leak” into the bloodstream, potentially leading to food sensitivities or even autoimmune reactions. Moreover, SIBO malabsorption can result in deficiencies in essential nutrients, such as iron and B12, leading to anemia, fatigue, and neurological symptoms.

Research is also uncovering connections between SIBO and other health conditions, such as rosacea, fibromyalgia, and chronic fatigue syndrome. These associations suggest that SIBO’s impact on health is multifaceted and may be related to nutrient malabsorption and chronic low-grade inflammation.

The Role of Complementary and Alternative Medicine in SIBO Treatment

Pharmaceutical Management

The cornerstone of pharmaceutical management for SIBO involves using antibiotics to reduce bacterial overgrowth and address any associated nutritional deficiencies. Among the antibiotics, rifaximin (Xifaxan) is the most commonly prescribed treatment for both hydrogen- and methane-dominant SIBO. Its effectiveness lies in its ability to target bacteria in the small intestine while exhibiting minimal systemic absorption, which reduces the risk of systemic side effects. For hydrogen-predominant SIBO, a regimen of rifaximin at 1650 mg per day for two weeks is considered an effective option. In cases of methane-predominant SIBO, combining rifaximin (1650 mg/day) with neomycin (1000 mg/day) for two weeks has shown promising efficacy due to their complementary antimicrobial actions.

Other antibiotics that may be utilized in SIBO management include metronidazole (Flagyl), tetracycline, amoxicillin-clavulanate, and neomycin. While these antibiotics can be effective, their use may be guided by patient-specific factors, bacterial susceptibility, and tolerance.

In addition to antibiotic therapy, addressing nutrient deficiencies caused or exacerbated by bacterial overgrowth and malabsorption is critical. Common deficiencies include vitamin B12, iron, thiamine (B1), niacin (B3), and fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K). Repletion of these nutrients is essential to correct the metabolic imbalances and systemic effects caused by SIBO.

Digestion Coach Important Message: It is essential to note that approximately 45% of patients experience SIBO recurrence after completing antibiotic therapy. Recurrence rates are notably higher in older adults, those with a history of appendectomy, or patients who are on chronic proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy. Given these challenges, the long-term management of SIBO often requires addressing underlying factors such as impaired motility, immune dysfunction, or anatomical abnormalities to prevent recurrence. Close monitoring and an integrated treatment approach can help achieve better outcomes.

Natural Antimicrobials Management

From the perspective of a long-time GI health expert, complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is gaining significant traction in the United States, with up to 50% of patients incorporating at least one form of alternative therapy into their healthcare regimen. In the context of SIBO treatment, herbal therapies have shown promise as a potential alternative to conventional antibiotics. Studies indicate that herbal treatments may be as effective as antibiotics, as evidenced by the normalization of lactulose breath test results, a standard diagnostic tool for detecting SIBO-related abnormalities.

Various herbs have well-documented antimicrobial properties that make them particularly effective in managing bacterial overgrowth. For example, oregano oil (Origanum vulgare) is a potent botanical that inhibits microbial growth and actively kills pathogenic bacteria in the gut. Similarly, Berberine extracts and Thymus vulgaris (thyme) possess broad-spectrum antibacterial activities, making them valuable tools for targeting a range of intestinal microbes. Wormwood (Artemisia absinthium) not only exhibits substantial antimicrobial activity but also possesses anti-inflammatory properties. Its multifaceted benefits have been demonstrated in gastrointestinal conditions like SIBO and even Crohn’s Disease, where it has been used to induce remission.

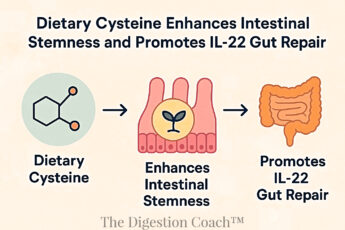

In addition to herbal therapies, other nutraceuticals have shown potential in supporting patients with SIBO and IBS-like symptoms. These include compounds with antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and antidiarrheal properties. For example, grapefruit seed extract, olive leaf extract (Olea europaea), and Pau d’Arco have demonstrated effectiveness in combating harmful bacteria. At the same time, beta-glucans and colostrum may modulate the immune system and support intestinal healing. Saccharomyces boulardii, a probiotic yeast, has been extensively studied for its ability to restore gut microbial balance and reduce intestinal inflammation.

By leveraging the benefits of these alternative therapies alongside conventional treatments, CAM approaches can offer a holistic strategy for managing SIBO. However, due to the complexity of SIBO and individual patient variability, collaboration with a healthcare professional experienced in integrative medicine is essential to optimize outcomes.

Dietary Management

Diet plays a supportive role in managing SIBO, but its effectiveness as a standalone treatment is limited. Following a low-FODMAP diet, which restricts fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols, has not been shown to resolve SIBO independently. While some patients experience symptomatic relief from bloating, gas, and abdominal pain due to reduced fermentation in the gut, the low-FODMAP approach is most effective when combined with antimicrobial therapies, such as antibiotics or herbal treatments, to address the underlying bacterial overgrowth.

An elemental diet may be considered in more challenging cases—such as when patients cannot tolerate antibiotics or fail to respond after two rounds of antibiotic therapy. An elemental diet provides easily absorbable nutrients in a liquid form, starving the bacteria by bypassing fermentation in the gut while supplying essential nutrition. Limited observational studies suggest that elemental diets can reduce SIBO symptoms, making them a potential option for treatment-resistant cases. However, its use is often restricted by several factors, including poor palatability, the monotony of the liquid diet, and high cost, which can affect patient compliance.

Ultimately, dietary approaches are most successful when tailored to individual needs and incorporated into a broader treatment strategy that addresses symptom management and the root causes of SIBO. To develop a comprehensive and sustainable treatment plan, it is recommended that a SIBO specialist be consulted.

The SIBO Cycle: Why Is Hard to Treat

As a digestion coach and doctor, I know that treating SIBO presents a unique set of challenges, primarily due to its cyclical and self-perpetuating nature. When bacteria ferment undigested food in the small intestine, the resulting gas buildup causes abdominal distension, further impairs intestinal motility. This reduced motility creates an ideal environment for additional bacterial overgrowth, fueling a vicious cycle that is difficult to break. Furthermore, bacterial overgrowth often triggers an inflammatory response that damages the intestinal lining, exacerbates dysbiosis, and makes restoring a healthy microbial balance even more complex.

Even after successful treatment with antibiotics or antimicrobial herbs to reduce the bacterial population, SIBO frequently recurs if the underlying factors—such as impaired motility, immune dysregulation, or dietary triggers—are not adequately addressed. Therefore, Effective management strategies must go beyond merely reducing bacterial levels; they must focus on restoring the migrating motor complex, balancing the immune system, and implementing sustainable dietary changes. Without these comprehensive interventions, bacterial overgrowth will likely return, leading to persistent or recurrent symptoms.

In summary, SIBO is more than just an overgrowth of bacteria; it represents a complex condition that disrupts the gut’s natural ecology, impairs nutrient absorption, and initiates a cascade of effects that can negatively impact overall health. Understanding these interconnected dynamics underscores the importance of adopting a multifaceted treatment approach. Collaborating with a SIBO specialist can provide tailored strategies to address the root causes, improve gut function, and achieve lasting symptom relief.

COMPLEMENTARY 15-MINUTE CALL

Take your first step toward a renewed sense of well-being. Call today to arrange a complimentary 15-minute consultation.

Let’s discern whether my approach aligns with your needs.

I look forward to connecting with you at 714-639-4360.

Stress Affects Digestion: Phases of Digestion – Part 1 of the 5