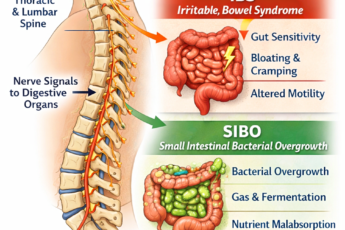

As a digestion coach and SIBO expert, I have treated hundreds of SIBO patients since before the term was used as a diagnosis. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) occurs when excessive bacteria accumulate in the small intestine, leading to a range of symptoms from mild discomfort to severe digestive distress. Once considered rare, SIBO is now recognized as a far more prevalent condition than previously thought. While its symptoms—such as bloating, chronic diarrhea, weight loss, and malabsorption—are well documented, the critical question remains: What are the predisposing factors that cause SIBO?

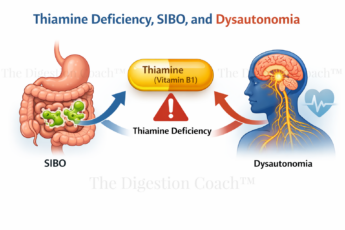

At its core, SIBO arises when the body’s natural mechanisms for regulating bacterial populations in the small intestine are disrupted. The two most significant predisposing factors that cause SIBO are diminished stomach acid secretion (including hydrochloric acid, potassium, and sodium chloride) and small intestinal dysmotility, which results in an increased transit time of food through the small intestine. These dysfunctions create an environment where bacteria can flourish unchecked.

Beyond these primary factors, other conditions can further predispose individuals to SIBO. These include immune disturbances affecting the small intestine, anatomical abnormalities of the gastrointestinal tract, chronic antibiotic use, and poorly controlled diabetes. Identifying these underlying contributors is crucial, especially when reduced stomach acid and dysmotility have been ruled out as primary drivers.

However, understanding the most common predisposing factors is only part of the equation. A more pressing question is: What causes these factors in the first place? What leads to impaired motility and reduced stomach acid production? Addressing these root causes is far more critical than simply managing the symptoms of SIBO. In the following sections, I will explore these fundamental triggers and their role in developing this condition.

Low Stomach Acid (Hypochlorhydria)

The four most common causes of low stomach acid production are antacid or PPI use, H. pylori infection, electrolyte balance (sodium, chloride, and potassium), and aging. The exciting thing here is that they all can and usually overlap. Low vagal tone, caused by stress (chronic sympathetic nervous system dominance), is another cause. I will have an article solely devoted to this very soon.

1. Chronic Exposure to PPIs or Acid Blockers, such as Prilosec, Zantac, or Tagamet. An overabundance of native or non-native bacteria within the small intestine can occur in as little as four weeks of PPI exposure. From my research, Zantac, an H2 blocker, is the safest and the least likely to contribute to SIBO. PPIs, especially omeprazole, are the worst offenders. Omeprazole is also a prescribed component of the Triple Therapy used for H. pylori eradication.

A simple experiment to see where your natural level of stomach acid (HCl) is to drink 1 tsp of Baking Soda in 3-4 ounces of water. The experiment should be done right when you wake up and once before bed – 1 tsp of Baking Soda each time. No matter what, this should be done on an empty stomach for optimum results. If your stomach acid levels are normal, you should get 1-3 good burps within 60-90 seconds after drinking the mixture – both times. If your morning drink does not produce 1-3 good burps, then your AM level of stomach acid is low. If your bedtime and morning mixtures don’t create 1-3 good burps, find a local functional medicine doctor who can help you diagnose the cause and get you on a restoration protocol, as you have low stomach acid production.

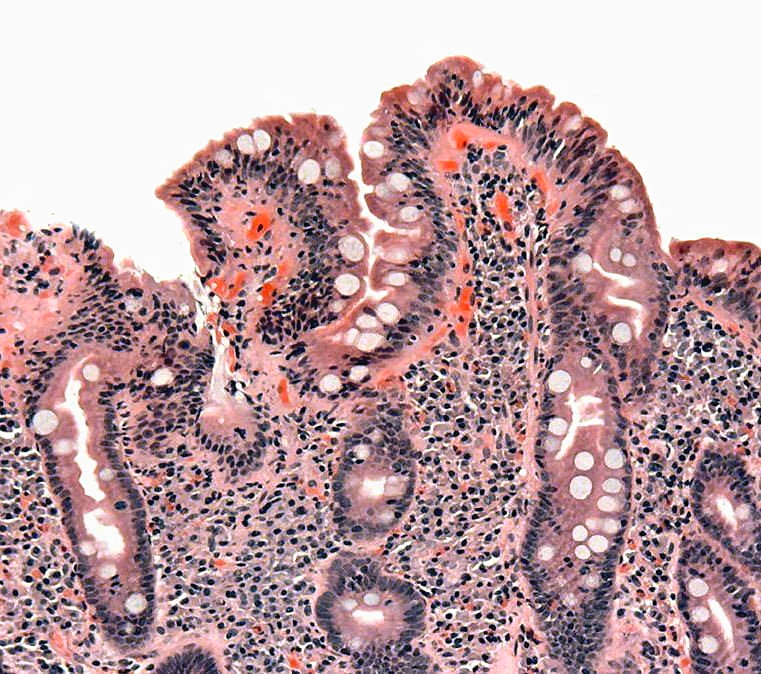

2. H. pylori Bacterial Infection. When this infection is in the body of the stomach (The body of the stomach makes up the majority of the familiar kidney-bean-shaped portion of the organ), it can cause hypochlorhydria due to the inflammation impairing the function of the parietal cells (which make HCl) and atrophy reducing their number. On the other hand, H. pylori infection of the pyloric antrum (opening to the body of the stomach) can cause the opposite effect, with too much gastric acid. A biopsy or Heidelberg test can help make this determination.

H. pylori can also neutralize stomach acid by producing large amounts of urease, which breaks down the urea in the stomach to carbon dioxide and ammonia. The ammonia, which has a very high pH, neutralizes stomach acid.

If H. pylori is present, it must be treated before or concurrently with a SIBO protocol.

3. Aging. Under normal circumstances, total gastrointestinal transit time in the elderly is that of a younger individual. It’s more likely that medications that slow GI motility, a decline in mobility, the onset of new diseases (e.g., diabetes), dietary changes that lead to malnutrition (Protein Digestion and SIBO), and changes in gut immune function are the primary triggers of SIBO as we age.

4. Other Factors that Cause SIBO.

- Food poisoning causes an acute autoimmune reaction within the small intestine. Food poisoning caused by any of these bacteria (E. coli, Salmonella, Shigella, or Campylobacter) produces a common toxin called Cdt-B toxin (Cytolethal Distending Toxin B). Once exposed to this toxin, susceptible individuals will produce antibodies to it. This leads to an acute reduction in intestinal motility, leading to the development of SIBO.

- Acute or chronic exposure to antibiotics.

- Chronic stress leads to a sympathetic nervous system-dominant state (flight-flight response). This leads to increased GI transit time, decreased nutrient absorption, decreased nutrient assimilation, leaky gut, and intestinal dysbiosis.

- A high FODMAP diet in suitable individuals.

The Overlap

Bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine is commonly associated with hypochlorhydria caused by atrophic gastritis (AG) or during treatment with PPI. AG can be caused by persistent infection with H. pylori or can be autoimmune in origin. Those with the autoimmune version of atrophic gastritis are statistically more likely to develop gastric carcinoma, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, and achlorhydria (lack of stomach acid).

Dysmotility (before SIBO)

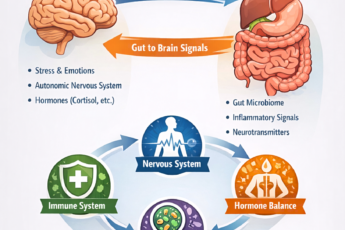

Gut-brain axis dysfunction occurs when the interpretation of neurologic messages from the GI tract to the brain and back to the GI tract is altered. This can alter the central and peripheral nervous system *tone, resulting in decreased function of the entire GI tract and glands associated with digestion. *In this context, tone refers explicitly to the continual nature of baseline parasympathetic action that the vagus nerve and central nervous system exert.

Gut-brain connection Imbalance is a stress-adaptation phenomenon. Too many factors may contribute to this. Below is a typical list of stress-related physical, behavioral, and emotional symptoms. If you have any of these symptoms, stress may be one of the factors that cause SIBO or other GI-related symptoms. Here is a link to the full article from Harvard Health Publishing: Gut-Brain Connection.

Physical symptoms

- Stiff or tense muscles, especially in the neck and shoulders

- Headaches

- Sleep problems

- Shakiness or tremors

- The recent loss of interest in sex

- Weight loss or gain

- Restlessness

Behavioral symptoms

- Procrastination

- Grinding teeth

- Difficulty completing work assignments

- Changes in the amount of alcohol or food you consume

- Taking up smoking or smoking more than usual

- Increased desire to be with or withdraw from others

- Rumination (frequent talking or brooding about stressful situations)

Emotional symptoms

- Crying

- An overwhelming sense of tension or pressure

- Trouble relaxing

- Nervousness

- Quick temper

- Depression

- Poor concentration

- Trouble remembering things

- Loss of sense of humor

If you experience any of the long-standing symptoms above, a stress management coach should be part of your health-restoration team. Exercise, yoga, tai chi, and other stress-reduction techniques should be implemented.

Gut health tip: certain nutritional support products may be indicated to help facilitate the repair and increased intestinal motility* or act as a stress-support crutch until other measures kick in. Please talk to your health coach before starting any nutritional protocol.

- Mucuna pruriens is a natural source of L-dopa. Its deficiency, for whatever reason, is a primary cause of the physical, behavioral, or emotional symptoms, such as those listed within the Gut-Brain Connection site.

- 5-HTP* is a precursor to serotonin, a happy neurotransmitter, and melatonin. 95% of the body’s serotonin lies within the GI tract.

- Lithium orotate, 5-10 mg, is a phenomenal product for keeping the brain’s communication channels open and healthy.

- Pantothenic acid (vitamin B5) is “the anti-stress vitamin.” B5 works with your LDL cholesterol to help make pregnenolone, DHEA, progesterone, cortisol, estrogen, testosterone, and aldosterone.

Note: 5-HTP may act as a mild prokinetic, meaning it helps movement through the small intestine. The GI tract tolerates 5-HTP supplementation and does not induce perpetual or excessive motility. Those with diarrhea should watch to see if 5-HTP increases bowel movements.

Alteration of The Migrating Motor Complexes (MMC). MMC are waves of electrical activity regulating stomach emptying and moving the contents down through the small intestine and into the large bowel. Every 90 minutes, during fasting, the MMC sweeps through the intestines, triggering peristaltic waves, which facilitate the transportation of chyme (digested food) and indigestible substances such as bone, fiber, and foreign bodies from the stomach through the small intestine, past the ileocecal sphincter, and into the colon. The MMC is thought to be partially regulated by motilin and ghrelin, initiated in the stomach as a response to vagus nerve (fight/flight nerve) stimulation.

Note: The MMC is at work when you experience stomach noise (hunger pains) about 4-5 hours after eating. If you do not feel movement just below the breastbone (sternum) at the margin of your left rib cage, your MMC may need tonifying.

Help: In omnivores and carnivores, the origin of the (MMC) is suppressed by the ingestion (eating) of a meal and returns after complete stomach emptying. Since most people are snaking or eating more than 2-3 meals daily, this complex may lose some of its integrity (tone). The key is to eat just 2-3 meals daily, with at least 12 hours between dinner and breakfast. I have seen this reestablish proper MMC integrity.

Help: Box Breathing (reproduced with grateful acknowledgment to Mark Divine and Sealfit)

Deep diaphragmatic breathing

Breathing is both a conscious and unconscious process. When unconscious, we tend to do “chest breathing.” This type of breathing is inefficient and labor-intensive, requiring more effort for the same amount of oxygen intake. It lowers energy stores and increases anxiety.

We should switch to a deep diaphragmatic breathing pattern for a stressful event.

We can practice a deep diaphragmatic breathing pattern through a discipline we call Box Breathing at SEALFIT Academy. Box breathing is meant to be done in a quiet and controlled setting, not while you are in the fight. The pattern is simply a box, whereby you inhale to a count of 5, hold for a count of 5, exhale to the exact five count, and hold again for 5. You can start at three if this is difficult or take it up a notch if it is easy. You should be uncomfortable on the exhale hold and be forced to fill the entirety of your lung capacity on the inhale hold.

The benefits of deep diaphragmatic box breathing include:

- Reduction of performance anxiety

- Control of the arousal response

- Increasing brain elasticity – flexibility through enhanced blood flow and reduced mental stimulation.

- Enhancing learning and skill development

- Increasing capacity for focused attention and long-term concentration

- Saltzman JR, Kowdley KV, Pedrosa MC, et al. Bacterial overgrowth without clinical malabsorption in elderly hypochlorhydric subjects. 1994;106:615–623. [PubMed]

- Dukowicz AC, Lacy BE, Levine GM. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth, A Comprehensive Review. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2007 Feb; 3(2): 112–122. [PubMed]

Factors that Cause SIBO Helpful Links

COMPLEMENTARY 15-MINUTE CALL

Take your first step toward a renewed sense of well-being. Call today to arrange a complimentary 15-minute consultation.

Let’s discern whether my approach aligns with your needs.

I look forward to connecting with you at 714-639-4360.