Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Composition and Characteristics of Feces

- Functions of the Large Bowel

- Role of Probiotic Bacteria in Digestion

- Energy Production and Disease Prevention

- Final Stages: Rectal Storage and Defecation

- Conclusion

- FAQs

Introduction

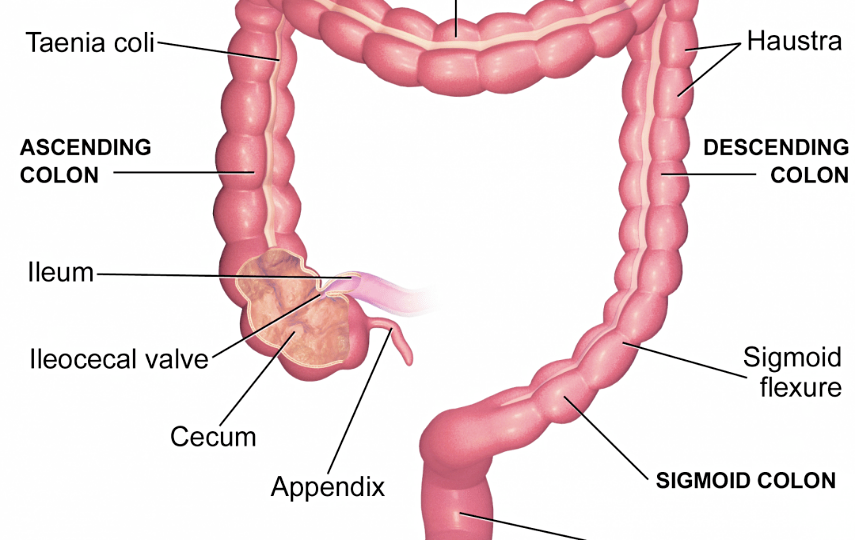

The large intestine, often referred to as the large bowel or colon, serves as the final segment of the gastrointestinal tract. It connects to the small intestine at the ileocecal valve and extends in a characteristic shape upward, across the abdominal cavity, and downward to terminate at the anus. Though shorter than the small intestine in length, measuring approximately 5 feet, the large bowel compensates with its substantial diameter of about 2.5 inches. This anatomical structure is integral to the complex process of digestion and waste elimination. The large bowel and digestion are intrinsically linked, forming a critical phase in the efficient processing of food and waste.

The lining of the large bowel differs significantly from that of the small intestine. Unlike the small intestine, which is covered in villi and microvilli to optimize nutrient absorption, the large bowel’s smooth lining is specialized for its unique role in digestion. The primary focus here is not the absorption of nutrients but the production and secretion of mucus. Abundant goblet cells within the large bowel’s lining release mucus to facilitate the passage of digested food remnants, termed chyme. This mucus acts as both a lubricant and protective barrier, shielding the intestinal walls from potential physical abrasion and the effects of bacterial fermentation. The large bowel and digestion rely heavily on this mucosal activity to ensure smooth transit of materials.

Composition and Characteristics of Feces

Healthy feces are a testament to the efficient functioning of the large intestine. Typically, feces comprise 75% water and 25% solid matter. Remarkably, approximately 50% of the solid portion consists of dead bacteria, commonly known as probiotics. The remaining solids are undigested organic material and dietary fiber. The brown hue of feces originates from the bacterial decomposition of bilirubin, a bile pigment. Characteristic odors arise from gases such as skatole, hydrogen sulfide, and thiols produced during bacterial metabolism. If excessive odor becomes an issue, adopting a diet rich in plant-based foods while reducing the intake of egg whites, garlic, and onions may mitigate this problem. Such adjustments underline the connection between dietary choices, the large bowel, and digestion.

Functions of the Large Bowel

The large intestine’s primary responsibility is to reclaim water and any residual absorbable nutrients from the chyme while preparing undigestible matter for elimination. Peristalsis, the coordinated contraction and relaxation of intestinal muscles, facilitates the gradual movement of chyme through the colon. Over several hours, this accordion-like motion ensures the efficient extraction of water and compacts waste material into feces. Occasionally, mass peristalsis can evacuate the colon more rapidly, often following a substantial meal or irritation.

Role of Probiotic Bacteria in Digestion

A defining feature of the large bowel is its dense population of probiotic bacteria, estimated to number 100 trillion, surpassing the total human body cells. These microbes contribute significantly to the digestion of substances left undigested by earlier stages of the gastrointestinal tract. Amylose, a complex starch comprising 20-30% of dietary starches, undergoes bacterial fermentation in the colon. This process not only converts chyme into feces but also generates essential vitamins such as K, B1, B2, B6, B12, and biotin (B7). Vitamin K synthesis, critical for blood clotting, highlights the symbiotic relationship between human health, the large bowel, and digestion. Consuming dark leafy greens can further support these beneficial bacterial processes.

Energy Production and Disease Prevention

Through bacterial fermentation, the large bowel contributes up to 10% of the body’s energy requirements by producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including butyric acid. These SCFAs are vital in promoting satiety and inhibiting the development of colorectal cancer. A diet abundant in fruits and vegetables supplies the necessary dietary fiber to sustain these microbial activities. This nutritional synergy emphasizes how the large bowel and digestion intersect with overall metabolic health and disease prevention.

Final Stages: Rectal Storage and Defecation

As digestion concludes, the large intestine stores dehydrated, condensed feces in the rectum. This waste is held until voluntary defecation removes it from the body. The efficient storage and elimination of waste are as essential to digestion as the earlier phases of nutrient absorption and energy extraction.

Conclusion

As a digestion coach, I look at the large bowel not merely as a passage for waste but as a dynamic organ crucial to digestion, microbial health, and overall well-being. Stress-free eating habits and a fiber-rich diet are paramount for optimizing the function of this vital organ. A harmonious balance of nutrients supports beneficial bacteria, promotes colon health, and sustains energy metabolism. Understanding the relationship between the large bowel and digestion illuminates the intricate processes sustaining human life and underscores the profound impact of dietary choices on our health.

FAQs

Why is the large bowel thicker than the small intestine?

Its thicker walls accommodate specialized functions such as water absorption, mucus production, and microbial fermentation, which are essential for the final phases of digestion.

What is the significance of probiotic bacteria in the large bowel?

Probiotics facilitate the fermentation of undigested materials, synthesize essential vitamins, and support immune function.

How does dietary fiber benefit the large bowel?

Fiber serves as fuel for beneficial bacteria, promoting SCFA production, supporting satiety, and reducing colon cancer risk.

What dietary changes can alleviate fecal odor?

Increasing plant-based foods and reducing sulfur-containing foods like egg whites, garlic, and onions can help mitigate strong odors.

How does the large bowel influence overall health?

Through microbial activity and nutrient recovery, the large bowel impacts immune defense, energy metabolism, and disease prevention.

Stress Affects Digestion: Phases of Digestion – Part 1 of the 5 Take your first step toward a renewed sense of well-being. Call today to arrange a complimentary 15-minute consultation. Let’s discern whether my approach aligns with your needs. I look forward to connecting with you at 714-639-4360.

Stomach, Saliva, and Mouth in Digestion: Part 2 and 3 of 5

The Small Intestine and Digestion – Part 4 of 5

COMPLEMENTARY 15-MINUTE CALL