Table of Contents

- The Small Intestine and Digestion – Introduction

- Size and Structure

- Primary Function: Nutrient Breakdown and Absorption

- The Duodenum – Neutralizing Acidity and Preparing for Digestion

- The Jejunum – The Heart of Nutrient Absorption

- The Ileum – Specialized Absorption and Transition to the Colon

- Stress Affects Digestion: A Critical Consideration

- Intestinal Permeability, Also Known as Leaky Gut

- Nutrient Absorption Impairment

- Absorption of Harmful Substances

- Altered Immune Function

- Mental Health Implications

- Dermatological Manifestations

- Food Intolerances and Sensitivities

- Autoimmune Diseases

- Chronic Inflammation and Cancer Risk

- The Role of Stress in Leaky Gut

- Small Intestine Fun Facts

- Conclusion

The Small Intestine and Digestion – Introduction

The small intestine, or small bowel, is a highly convoluted, tubular structure within the digestive tract. The primary responsibility of the small intestine via digestion is to absorb approximately 90% of the nutrients from the food we consume, though its role extends far beyond nutrient absorption. This organ represents our immune system’s most significant and active part, acting as a frontline barrier against pathogens. Additionally, the small intestine influences our emotional state through its intricate connection with the gut-brain axis, underscoring its importance in overall mental health. As a GI health specialist, I am always fascinated by this organ’s multifaceted contributions to physical and emotional well-being. It’s nothing short of remarkable and is always in my mind when building a protocol to support a patient’s gut and emotional health.

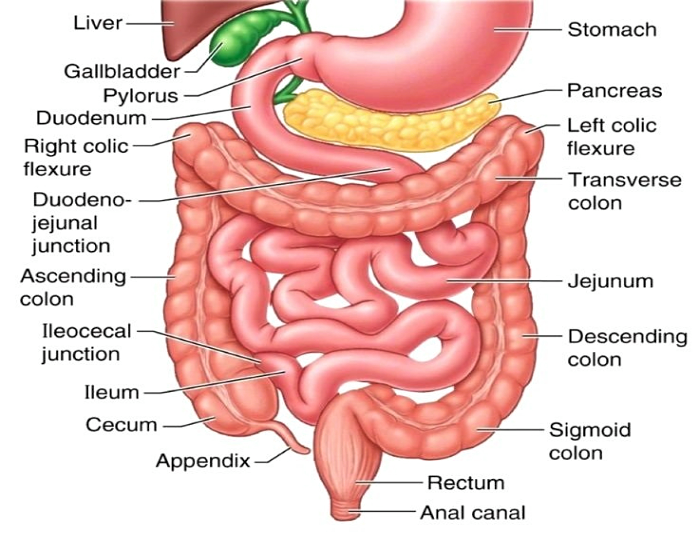

Size and Structure

Contrary to what its name might suggest, the small intestine is not “small” in length—it spans approximately 20-22 feet in an adult, making it over twice as long as the large intestine. However, its diameter is significantly smaller, measuring only about 1 inch, compared to the 2.5-inch diameter of the large intestine. This stark contrast in diameter explains its “small” designation. The small intestine’s extensive length is essential for its primary function: providing ample surface area to maximize nutrient absorption. To put its length in perspective, it’s comparable to the size of a 1979 Barth RV, emphasizing its impressive expanse within the human body.

Primary Function: Nutrient Breakdown and Absorption

The main role of the small intestine is to break down ingested food into its basic building blocks: proteins into peptides, carbohydrates into monosaccharides, and fats into fatty acids. These units are small enough to be absorbed by specialized cells lining the intestinal wall. This critical process is contingent upon the effective function of earlier digestive steps in the stomach, which transform the food into a semi-liquid mixture called chyme. If any part of this digestive chain falters—whether due to enzyme deficiencies, pH imbalances, or structural issues—the small intestine’s ability to absorb nutrients is significantly impaired.

The Duodenum – Neutralizing Acidity and Preparing for Digestion

The journey of digestion in the small intestine begins in the duodenum, the shortest yet most active segment. Chyme entering the duodenum from the stomach is highly acidic, a byproduct of gastric acid secretion. This acidic mixture must be neutralized to prevent damage to the delicate intestinal lining. The liver, gallbladder, and pancreas play pivotal roles at this stage. The bile duct and pancreatic duct release bile, pancreatic enzymes, and bicarbonate into the duodenum. Bile emulsifies fats, facilitating their breakdown, while bicarbonate raises the pH to a more neutral level suitable for enzymatic activity. Pancreatic enzymes, including amylase, lipase, and proteases, further digest carbohydrates, fats, and proteins, respectively. The health of these accessory organs—supported by a balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, healthy fats, regular exercise, adequate hydration, and quality sleep—is indispensable for optimal digestive function.

The Jejunum – The Heart of Nutrient Absorption

After preliminary digestion in the duodenum, chyme enters the jejunum, the second segment of the small intestine. This region is where the majority of nutrient absorption occurs. The jejunum is lined with villi and microvilli—microscopic, finger-like projections that significantly increase the surface area for absorption. These structures house enterocytes, specialized intestinal cells that actively transport nutrients such as glucose, amino acids, and lipids into the bloodstream. The efficiency of this process depends on various factors, including enzyme activity, the structural integrity of the villi, and the proper functioning of transport proteins. Remarkably, the surface area of the small intestine, when flattened, is estimated to be the size of a tennis court, underscoring its adaptive design for nutrient absorption.

The Ileum – Specialized Absorption and Transition to the Colon

The ileum, the final segment of the small intestine, is tasked with absorbing specific nutrients, such as vitamin B12 and bile salts. Vitamin B12 absorption is a complex process that requires the presence of intrinsic factor, a glycoprotein secreted by the stomach. Bile salts, crucial for fat digestion, are reabsorbed in the ileum and recycled via the enterohepatic circulation. The ileum also contains a significant number of lymphoid follicles, known as Peyer’s patches, which are critical for immune surveillance and defense against pathogens. As chyme moves through the ileum, strong muscular contractions, known as peristalsis, propel the remaining nutrient-rich contents toward the ileocecal valve. This valve regulates the passage of material into the large intestine while preventing backflow, ensuring efficient digestion and absorption.

Stress Affects Digestion: A Critical Consideration

External factors, including stress, can significantly influence small intestine digestion and efficiency. Chronic stress triggers the release of cortisol and other stress hormones, disrupting the gut’s motility and enzymatic activity. Stress may reduce blood flow to the digestive tract, impairing the secretion of digestive enzymes and bicarbonate. Additionally, stress alters the composition of the gut microbiota, potentially leading to dysbiosis—a condition where harmful bacteria outnumber beneficial microbes. Dysbiosis hampers nutrient absorption and compromises the intestinal barrier, increasing the risk of systemic inflammation. The gut-brain axis, mediated by the vagus nerve, further highlights the bidirectional relationship between stress and gut health. For instance, stress-induced changes in gut function can exacerbate anxiety and depression, creating a vicious cycle that underscores the importance of managing stress for digestive health.

Recognizing the interplay between stress and digestion and understanding the intricate physiology of the small intestine can help us gain a deeper appreciation for the complexity of this vital organ and its profound influence on overall health.

Intestinal Permeability, Also Known as Leaky Gut

Intestinal permeability, commonly called “leaky gut,” arises when the tight junctions between epithelial cells lining the intestinal wall become compromised. Typically, these tight junctions act as selective gates, permitting the passage of nutrients and beneficial molecules while keeping harmful substances, such as pathogens, toxins, and undigested food particles, out of the bloodstream. The intestinal lining becomes porous when this barrier is compromised due to a poor diet, antibiotic use, gluten exposure, pesticides (notably glyphosate), heavy metal toxicity, or chronic stress. This increased permeability allows undesirable substances to enter the bloodstream, triggering a cascade of physiological consequences.

Nutrient Absorption Impairment

One of the most immediate consequences of a leaky gut is the diminished ability to absorb nutrients effectively. Damage to the villi and microvilli—the finger-like projections that increase the absorptive surface area of the intestine—means fewer nutrients, including vitamins, minerals, and macronutrients, are taken into the bloodstream. Over time, this can lead to deficiencies in essential nutrients such as iron, zinc, magnesium, and B vitamins, critical for maintaining cellular functions, energy production, and overall health.

Absorption of Harmful Substances

With a compromised intestinal barrier, harmful substances such as antigens (foreign proteins), lipopolysaccharides (components of bacterial cell walls), and partially digested food particles can leak into the bloodstream. These substances are recognized by the immune system as invaders, prompting an immune response. Chronic exposure to these antigens leads to systemic inflammation, a root cause of many health issues. Lipopolysaccharides, in particular, have been linked to metabolic disorders, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular diseases due to their ability to elicit strong inflammatory responses.

Altered Immune Function

Approximately 70-80% of the body’s immune cells reside in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT), making the intestine a critical hub for immune function. When the intestinal barrier is compromised, the immune system becomes hyperactive, constantly responding to the influx of antigens. This overactivation can lead to a dysregulated immune response, contributing to conditions such as asthma, allergies, and autoimmune diseases. In autoimmune disorders, the immune system mistakenly attacks the body’s own tissues, a process that is thought to be triggered or exacerbated by the molecular mimicry of foreign proteins crossing the leaky gut barrier.

Mental Health Implications

The gut-brain axis, a bidirectional communication network between the gut and the brain, plays a pivotal role in mental health. A leaky gut allows pro-inflammatory cytokines and microbial byproducts to enter the bloodstream, some of which can cross the blood-brain barrier. This can lead to neuroinflammation, which has been associated with conditions such as depression, anxiety, attention-deficit disorders (ADD/ADHD), phobias, and even suicide. Chronic stress further compounds this issue by disrupting gut motility, altering the gut microbiome, and increasing intestinal permeability. Stress-induced gut dysfunction exemplifies the complex interplay between emotional and digestive health.

Dermatological Manifestations

The skin, often referred to as the “window to the gut,” is another organ that reflects the health of the intestinal barrier. A leaky gut has been linked to various skin conditions, including acne, eczema, psoriasis, boils, and rashes. This connection is mediated by systemic inflammation and the immune system’s heightened response to antigens and toxins leaking into the bloodstream. For instance, inflammatory cytokines can trigger the release of histamine, exacerbating skin conditions like eczema or hives.

Food Intolerances and Sensitivities

A damaged small intestine barrier can contribute to the development of digestion dysfunction and food intolerances. Lactose (milk sugar) and fructose (fruit sugar) intolerances are particularly common in individuals with leaky gut, as damage to the intestinal lining reduces the production of digestive enzymes such as lactase. Additionally, the immune system may start to produce antibodies against specific food proteins that have crossed the gut barrier, leading to food sensitivities or allergies that were not previously present.

Autoimmune Diseases

The link between leaky gut and autoimmune diseases is a subject of intense scientific investigation. Conditions such as multiple sclerosis, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, celiac disease, and type 1 diabetes have been associated with increased intestinal permeability. In these conditions, the immune system targets body tissues that share structural similarities with antigens that have breached the intestinal barrier, a process known as molecular mimicry. Repairing the intestinal lining through diet, probiotics, and stress management may play a role in mitigating the progression of these autoimmune diseases.

Chronic Inflammation and Cancer Risk

Chronic low-grade inflammation is a hallmark of leaky gut. Persistent immune activation and systemic inflammation can contribute to metabolic disorders, cardiovascular disease, and neurodegenerative conditions. Furthermore, prolonged exposure to toxins and carcinogens entering the bloodstream through a compromised gut barrier may increase the risk of certain cancers, particularly gastrointestinal cancers. The inflammatory environment created by leaky gut is thought to facilitate cellular damage and mutations that drive cancer progression.

The Role of Stress in Leaky Gut

Stress is a major contributor to intestinal permeability. Chronic stress elevates cortisol levels, weakening the tight junctions between intestinal epithelial cells. Additionally, stress reduces blood flow to the gastrointestinal tract, impairs the secretion of digestive enzymes, and disrupts the gut microbiota, all of which exacerbate leaky gut. Managing stress through techniques such as mindfulness, yoga, or therapy is critical to restoring intestinal health and preventing the cascade of adverse health outcomes associated with leaky gut.

As a digestion coach and doctor, I know better than most that understanding the intricate biology of leaky gut (intestinal permeability) and its far-reaching consequences can help us appreciate the critical role that intestinal health plays in overall well-being. Addressing leaky gut through dietary changes, gut-friendly supplements, and stress management is my 1, 2, and 3 essentials for preventing and managing the diverse range of conditions associated with this pervasive yet often overlooked issue.

Small Intestine Fun Facts

- Digestive Secretions: The Liquid Symphony of Digestion

In a healthy adult, the small intestine processes an impressive 1 gallon of digestive secretions daily to handle the 2-3 quarts of food and drink consumed. This volume includes 2 cups of saliva, 8 cups of stomach acid (HCl), and 6 cups of pancreatic and gallbladder secretions. These fluids play a critical role in breaking down food into absorbable nutrients.

- Saliva: Initiates carbohydrate digestion with the enzyme amylase and lubricates food for smooth passage through the esophagus.

- Stomach Acid (HCl): Activates pepsinogen into pepsin for protein breakdown and sterilizes ingested food by killing pathogens.

- Pancreatic and Gallbladder Secretions: These include bicarbonate to neutralize stomach acid, enzymes like lipase, protease, and amylase for macronutrient digestion, and bile for emulsifying fats into absorbable micelles.

Stress affects digestion by altering the production of these vital secretions. Chronic stress can suppress salivary and pancreatic enzyme output, reduce bile flow, and impair the stomach’s acid production, leading to maldigestion and nutrient deficiencies.

- Sodium: The Driver of Nutrient Uptake

Sodium is a crucial element for nutrient absorption in the small intestine. It serves as a co-transporter, facilitating the uptake of proteins (as amino acids), sugars (as monosaccharides like glucose), and fats (as fatty acids and glycerol). Sodium-dependent transporters rely on the electrochemical gradient established by the sodium-potassium pump, which actively moves sodium out of enterocytes, allowing nutrients to flow into the bloodstream and lymphatic system.

Stress can disrupt sodium balance through hormonal effects, mainly via cortisol and aldosterone, which regulate sodium retention and loss. Prolonged stress-induced imbalances may impair nutrient uptake efficiency, exacerbating deficiencies over time.

- Immune Stronghold: The Gut-Associated Immune System

Over 70% of the body’s immune system resides in the small intestine, concentrated within the gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT). This system includes Peyer’s patches, dendritic cells, macrophages, and lymphocytes that identify and neutralize harmful pathogens. The intestinal barrier, composed of epithelial cells, tight junctions, and mucous layers, works in tandem with GALT to maintain a balanced immune response.

Stress affects digestion and gut immunity by weakening the intestinal barrier through cortisol-mediated disruption of tight junctions. This increases intestinal permeability, allowing pathogens and antigens to trigger excessive immune responses, leading to systemic inflammation and autoimmune conditions.

- The Gut-Brain Axis: Neuronal Richness of the Small Intestine

The small intestine contains a staggering 100 million neurons—more than the spinal cord—earning its nickname as the “second brain.” These neurons form the enteric nervous system (ENS), a semi-autonomous network that governs gut motility, secretion, and absorption. The ENS communicates bidirectionally with the central nervous system (CNS) via the vagus nerve, integrating digestive and emotional health.

Expressions like “gut instinct” or “gut feeling” stem from this complex neural network. Stress affects digestion through the ENS by modulating gut motility and secretory functions. Acute stress can accelerate motility, leading to diarrhea, while chronic stress may inhibit it, causing constipation.

- Serotonin: The Digestive Neurotransmitter

Approximately 95% of the body’s serotonin—a neurotransmitter crucial for mood regulation and peristalsis—is produced in the small intestine by enterochromaffin cells. Serotonin initiates the rhythmic contractions of peristalsis, propelling chyme through the digestive tract. Insufficient serotonin can lead to constipation, while excessive serotonin release, often triggered by acute stress or fear, can result in diarrhea.

The vagus nerve plays a pivotal role in regulating intestinal serotonin circuits. Stress-induced overactivation of these circuits can cause intestinal distress, highlighting the gut-brain connection. Interestingly, medications like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), including Prozac, affect serotonin receptors in the gut and the brain. At low doses, these drugs can treat chronic constipation by stimulating peristalsis, but at higher doses, they may cause constipation by desensitizing serotonin receptors.

- Gut-Derived Benzodiazepines: Nature’s Tranquilizers

The gut produces benzodiazepine-like compounds, which belong to the same chemical family as pharmaceuticals like Valium and Xanax. These psychoactive substances bind to GABA receptors, exerting calming effects on the nervous system. This natural production underscores the gut’s role in managing stress and emotional states. However, chronic stress can deplete the gut’s ability to produce these tranquilizers, potentially contributing to heightened anxiety and stress-related disorders.

- The Gut’s Role in Pharmacology and Health

The dual action of Prozac in both the brain and the gut illustrates the overlap between gastrointestinal and psychological health. By modulating serotonin levels in the small intestine, Prozac can influence both digestive motility and mood. However, the paradoxical effects of SSRIs—treating constipation at low doses while causing it at higher doses—highlight the need for careful dose management.

Chronic stress exacerbates these effects by dysregulating serotonin production and receptor sensitivity in the gut, further complicating the interplay between the small intestine, digestion, and mental health. Addressing stress through lifestyle changes, dietary interventions, and mindfulness practices can help restore balance to this delicate system.

Conclusion

The small intestine is a physiological marvel, intricately connected to nearly every system in the body. Its roles extend beyond digestion to immune defense, neural communication, and emotional regulation. Through the small intestines’ pervasive effects on digestion, immunity, and neurotransmitter balance, stress underscores the importance of maintaining gut health as a cornerstone of overall well-being. Understanding these connections gives us insight into the profound relationship between the mind, body, and digestive system.

COMPLEMENTARY 15-MINUTE CALL

Take your first step toward a renewed sense of well-being. Call today to arrange a complimentary 15-minute consultation.

Let’s discern whether my approach aligns with your needs.

I look forward to connecting with you at 714-639-4360.

Stress Affects Digestion: Phases of Digestion – Part 1 of the 5

Stomach, Saliva, and Mouth in Digestion: Part 2 and 3 of 5

Large Bowel and Digestion – Part 5 of 5